- Home A world held together by ropes and knots by Piers Vitebsky

by Piers Vitebsky

There are very few people I would take with me on an anthropological expedition to the far northeast of Siberia. Laurence Edwards is not only a great artist, but also an uncomplaining travelling companion and a humane observer of people and their environment.

Again and again, I saw how Laurence would study people’s faces, but how his gaze would also be drawn to the knives and axes in their hands, and on to the textures and substances of the land beyond: the moss, lichen, twigs and stones, the hides and hacked-off fragments of animals encrusted with dried blood and lying around ready to be used as the fundamental materials for making tools and equipment, in order to catch yet more of the animals which are the only support for humans on this vast, dangerous and almost uninhabited landscape.

Confronted with the unhurried pace of the herders, where the processes of life and death and the mechanisms of the flesh are so starkly revealed, Laurence’s reaction made me think anew about the constant tying and untying of the ropes which hold a herder’s world together, and which I had come to take for granted: the reindeer-hide thongs repaired and tangled over many years of migration, on saddlebags, in the complicated skeins of harnesses, and in the erecting and dismantling of a tent; the knots tied with a single loop which hold firm yet pull apart with a sharp tug at the free end, but which must be picked apart with painful bare hands when they become encrusted with the ice of a day’s travelling; the cords holding wooden sledges together loosely so that they yield instead of shattering when they bang against the jagged rocks masked under a blanket of snow.

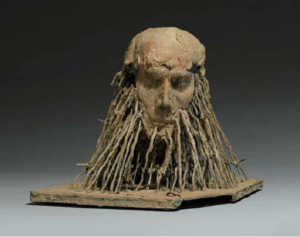

Lacuna and Laughing Strings use ropes and twigs to create form and substance, just as the herders do. But there is the nervous undertow of a newcomer responding in fascination to this environment: tendons are stripped bare, exposed, hollowed out with all the stitching showing. In Shuttle, inspired by the design of a fish trap, the human figure is suspended – safely cocooned, or imprisoned? Reindeer are regularly tied and released, tied and released, meanwhile roaming forty miles a day to graze. In Caravan, people are grouped together just as reindeer are harnessed to a caravan of sledges. But is Caravan an echo of reindeer teamwork, or does the all-encompassing rope signify a more total entrapment? Again, in Coil and The Snag,

it is a human who is held fast, rather than an animal.

A lasso is made from a long, thin strip of reindeer hide, and is known as the “long arm of the herder”. It is coiled and thrown slightly ahead of a running reindeer, to allow time for the noose to swoop over the antlers and fall around their root, snapping shut through a toggle carved from mountain sheep’s horn without falling further down around the animal’s neck. The reindeer is held fast by the tension caused by its own strugggle as the herder draws himself and the animal together by pulling hand over hand along the rope. In Laurence’s Lasso, is it the man who is trapped? But also he is the lasso, and he is the antler – he is all the parts in the entire drama of catching, holding and releasing.

Yet by constraining an animal force which would otherwise roam beyond human control or engagement, ropes and knots are also liberating, and the local cosmology seems designed to face this ambiguity.

Wild animals cooperate in their own catching at the command of their spirit master, an old man called Bayanay who sends them to offer themselves to the hunter willingly. A skilful hunter treats the animal’s flesh, bones and soul with gestures of respect, so that Bayanay will make sure it is reincarnated as the same species next time round and offer itself to the same hunter again. Domestic reindeer are caught by lasso and harnessed by a tangle of straps and knots, but they too cooperate with their human minders in a symbiotic ecology of mood. Some come to be milked by women, others are trained to pull sledges or to work closely with a rider clad in matching reindeer fur, so that they glide smoothly like an antlered centaur. Some people have a special magic reindeer which acts as an animal double and life insurance policy, deliberately standing in front of its human companion when that person is threatened with accident or disaster, taking the blow and dying in its owner’s stead.

Laurence’s figures are human, but perhaps even more than he realises, they pick up indigenous ideas of the interchangeability of human and animal identity and form. The lives of both animals and humans are defined by ropes and knots, which entrap and liberate them at the same time.

Dr Piers Vitebsky is Head of Anthropology and Russian Northern Studies at the Scott Polar Research Institute