Receive the latest information and updates about the artist

Follow

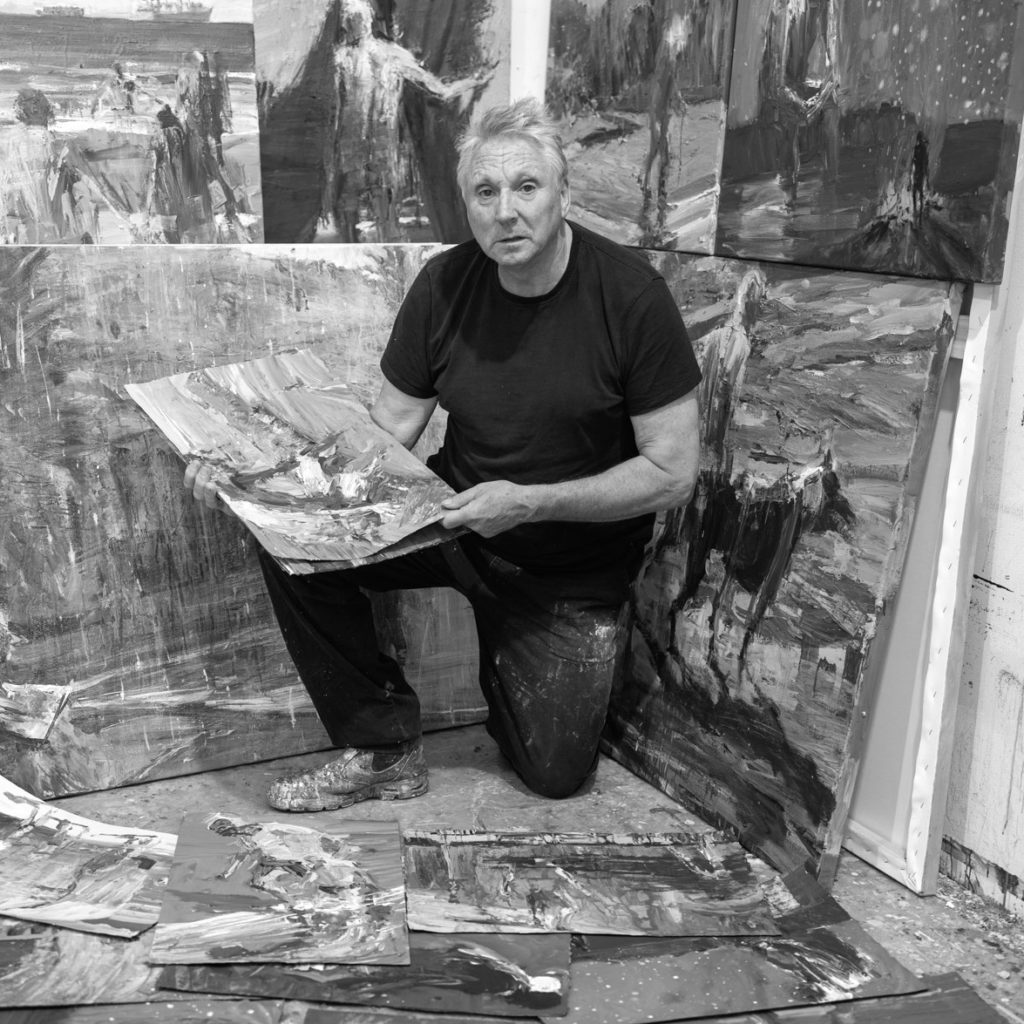

Euan Macleod was born in Christchurch, New Zealand in 1956. He was awarded a Diploma of Fine Arts (Painting) by the Ilam School of Fine Arts, Canterbury University, in 1979, before moving to Sydney in 1981. He has held more than fifty solo shows in New Zealand and Australia and has taken part in numerous group exhibitions in Australasia and internationally.

Macleod’s work is represented in many private and public collections, including the National Gallery of Australia, Te Papa Tongarewa Museum of New Zealand, and the Metropolitan Museum, New York. Euan has won art prizes in Australia, including the Archibald in 1999, the Sulman Prize in 2001, the Blake Prize in 2006, the New South Wales Parliament’s inaugural Plein Air painting prize in 2008, the Tattersall’s Landscape Prize in 2000 and 2009, the Gallipoli Art Prize, 2009, and the King’s School Art Prize in 2011.

In 2010 Piper Press, Sydney, published a monograph, Euan Macleod: the Painter in the Painting, written by Gregory O’Brien.

Surface Tension: the art of Euan Macleod 1991-2009, a Tweed River Art Gallery touring exhibition, curated by Gavin Wilson, toured six regional Australian galleries, beginning at the S H Irvin Gallery, Sydney, in November 2010.

The touring exhibition, Euan Macleod – Painter, curated by Gregory O’Brien, travelled to several New Zealand regional galleries between 2014 and 2017.

In 2019 Macleod collaborated on High Wire, a book of drawings and words, with Lloyd Jones. It was published in 2020.

‘Euan Macleod paints from the core of his being, taking us into innermost regions of the human condition. His works explore states of youth and aging, the relationship between humanity and the environment, and the processes of memory and forgetting which shape both people and places.’ Gregory O’Brien.

Photo of the artist: Andrew Merry

Euan Macleod – Internal Landscape

Euan Macleod spent his early years walking and climbing the alpine and coastal areas of New Zealand’s South Island. Drawn to mountaineering from a young age, he developed an affinity with remote wilderness areas which are now integral to his painting.

Returning to these sites and working en plein air with extraordinary speed, Macleod uses the physical challenges, unpredictable weather conditions and rapidly changing light to guide his painting and galvanise his attention. His ability to create works such as these while buffeted by a howling wind along a coastline, or perched on a shale blade above a glacier is astonishing, suggesting a willingness to surrender to the elemental forces of a particular place, rather than to merely make pictures of it.

Macleod maintains a fascination with potentially dangerous environments where he is often alone or linked by a rope to a companion figure or guide. This carries over into his work as a recurring metaphor where the connection to and reliance on another human being is amplified.

Recently Macleod returned to the Haupapa Tasman Glacier in the Westland Tai Poutini National Park in New Zealand’s South Island. This is a sublime and inhospitable world of minerals, rock and ice. Sedimentary layers of densely compacted snow in the glacier reveal a dirty pink line from three years earlier, marking Macleod’s previous visit during which a dumping of red ash was borne on the wind from the horrific Australian bush fires 2000km away. It is a landscape of extreme power that plays out over vertical intervals and timescales, but Macleod has also increasingly observed a fragility in this environment with each visit.

Throughout the day and night, the surrounding mountains and glaciers constantly bust, click and crack under staggering forces that can open up a 20-metre-deep crevasse in an instant. Dark clouds billow and suddenly evaporate into a crystalline sky. Far below, braided rivers of glacial melt wend their way in putty-coloured ribbons along the valley floor away from the receding moraine walls, an unsettling reminder of the accelerating impact of a warming climate.

In this shifting and dramatic environment Macleod sets to work, responding to and being guided by the changes unfolding before him in the landscape, and looking to capture the quality of the place. Working quickly in acrylics he loads the paper with paint, giving over control and allowing the fluid colours to coalesce. There follows a struggle as he works to draw the landscape topography out of the initial chaos, alternating between three to four images at a time which lie about him in various stages of drying, weighted down by stones.

The sudden appearance of a displaced and wandering figure, a hallmark of Macleod’s work, radically alters what began as a landscape painting, setting off an altogether different reading and drawing us into something similar to a vignette in which a wider narrative or context is withheld. It is as though we have stumbled into someone else’s dream with only fragments to go on.

The landscapes traversed by Macleod’s figures in these, and other paintings are understood to be extensions of their psychology through the way in which their physical forms are rendered in various stages of manifestation or dissipation. Some appear in the paintings as pure cloud, rock or shadow. The landscape has been transformed into a psychological setting which these ghostlike apparitions are compelled to navigate. In one painting a solitary figure makes its way along the edges of a crevasse. In another, a naked form gingerly picks its way through ice and scree. Gazing from an outcrop over enormous chunks of ice and rockfall, a man is stupefied by the landscape in which he finds himself. Elsewhere a colossus slumps on a headland, staring mutely at an absurdly small figure in the bay.

Macleod speaks of a lifelong sense of unease that he has experienced from an early age, and which is pervasive in his work; a feeling that something is not quite right in the world but which sits off to the side of the mind, operating in a blind spot or shadow. Through the act of painting he turns to face this disquiet, making it the subject while harnessing it as an energy source with which to produce the work. The restlessness from within his internal landscape is activated and summoned in those places where he is pushed to his limit, with the painting acting as the space where mirrored worlds meet.

Bradley Hammond

2 April 2023