Receive the latest information and updates about the artist

Follow

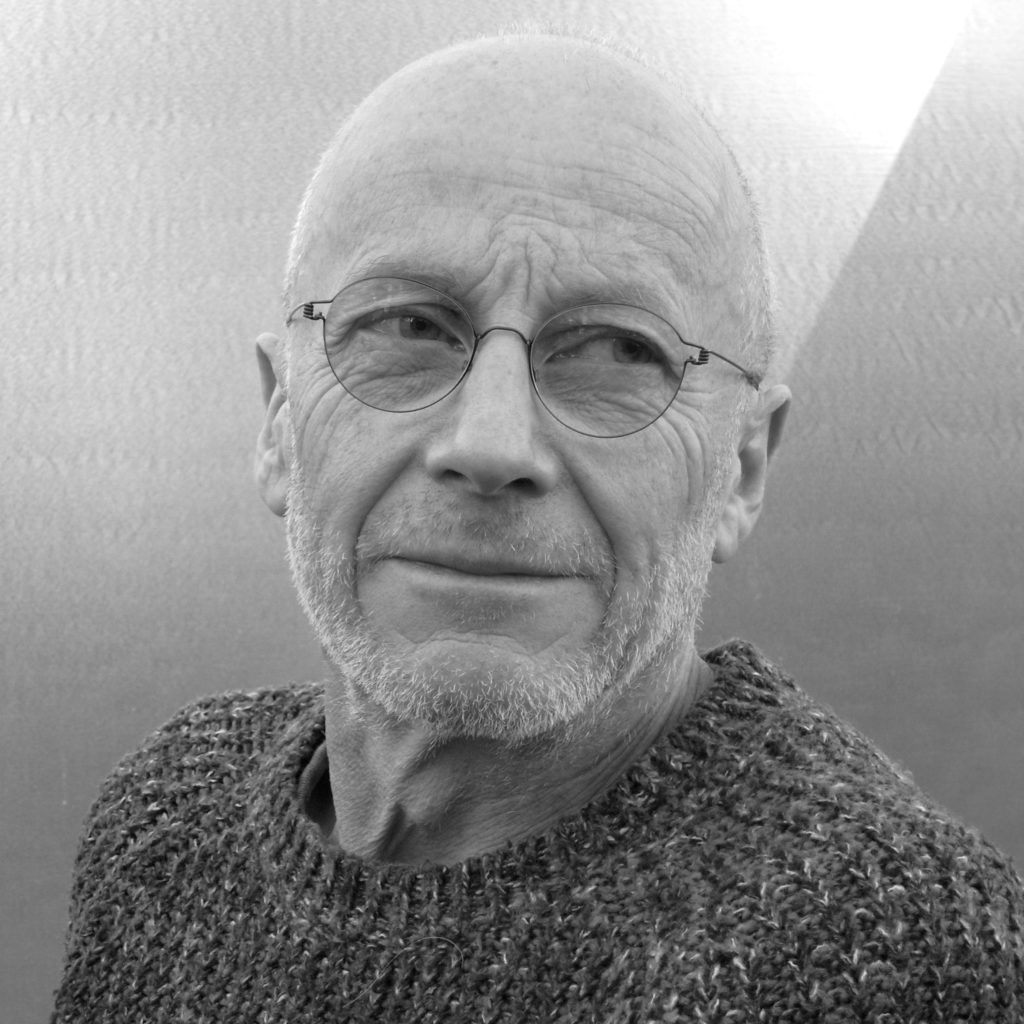

Martin Smith has achieved international recognition as one of the UK’s leading ceramic artists. His innovative and influential career has been compared to that of the late Hans Coper by Chris Dercon, who also described him as ‘… the most abstract and geometrically orientated ceramist in England and possibly of our times.’

He trained at Bristol Polytechnic Faculty of Art and Design and the Royal College of Art, and sees himself as an artist, making his work with the mindset of an architect and meticulously planning each piece.

Since the start of his career in the late 1970s, Smith has exhibited internationally, and examples of his work can be found in many public collections worldwide. A major retrospective was held at the Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, Rotterdam, in 1996 and in 2001 he made Wavelength, a site-specific work for Tate St. Ives.

His continuing practice in the field of ceramics consists of an on-going project investigating the formal language of the vessel and the way that it can both contain a space and define a place. Investigations into both material and process underpin his work.

BIOGRAPHY

1950 Born Braintree, Essex

1970-71 Ipswich School of Art

1971-74 Bristol Polytechnic, Faculty of Art and Design. Dip AD(Ceramics)

1975-77 Royal College of Art. MA(RCA)

MAIN TEACHING POSTS

2015-18 Royal College of Art Senior Research Fellow

1999-15 Royal College of Art, London Professor of Ceramics and Glass

1996-99 Royal College of Art, London Deputy Course Director, Ceramics and Glass

1989-96 Royal College of Art, London Senior Tutor, Ceramics and Glass

1986-89 Camberwell School of Art and Crafts Senior Lecturer, Ceramics

1983-85 Loughborough College of Art and Design

Senior Lecturer, Ceramics

1980-83 Brighton Polytechnic

1979-80 Camberwell School of Art and Crafts

1977-83 Loughborough College of Art and Design

Martin Smith Q&A

by Dr Claudia Milburn

Q. What first inspired your practice as a ceramicist, and when was this?

A. I first became aware of working with clay during the time I was studying for my A levels in physics, pure mathematics and geography. One afternoon a week was set aside for something else that I think was called liberal studies and aimed to give a broader education. I chose to spend the time in the college ceramics department and something clicked.

Q. What is your background / training and how influential has that been?

A. Following my A levels I had an abortive period at a teacher training college with a view to becoming a geography teacher – I dropped out after a horrendous term of teaching experience and then spent time working as a painter, decorator and builders assistant before enrolling on a Foundation course at Ipswich School of Art. Although I saw this as a route to being able to study ceramics at a higher level, the course was built on fundamental Bauhaus principles that gave a good grounding in a wide range of art and design principles and subjects.

From Ipswich I progressed to Bristol Polytechnic and the Dip AD course in Ceramics with a view to becoming a studio potter in the Leach tradition, making domestic pots for use. However, the course was so much more than this. To begin with, Gillian Lowndes was on the staff and ran the first projects. Gordon Baldwin made regular visits and during one tutorial made the statement that I still remember “…. As soon as you realize that the reason you make something is because that’s what you do, its time to stop and think…”. The second year of the course was dedicated to Design and industrial production with factory visits to a still thriving Stoke-on-Trent. This opened my mind to a totally different way of working with clay – the use of molds, machines, repetition and precision. It was also during this period that I spent vacation periods working for Robin Welch at his pottery in Suffolk producing ware for his domestic range. Although this worked with a lot of the characteristics of current studio pottery, namely reduction fired stoneware with ash glazes it followed a modular design system that used a combination of jigger and jolly and precision throwing of cylindrical vases and jugs. I suppose it was these experiences that opened my mind to the possibilities on working clay with real precision rather than reveling in just its plastic nature.

During my final months at Bristol I produced a body of work using the old Japanese technique of Raku and it was this that developed during my time at the Royal College of Art. I undertook a Degree by Project which in effect was the equivalent of an MPhil but at that time research degrees were unavailable in Art and Design. The project was to investigate and develop ways of bringing control and precision to the Raku technique.

Q. You have been described as a ceramic artist who makes work with the mindset of an architect. Can you elaborate on this?

A. I think in some way this description refers to the spatial concerns of place and space that underpins my work and also to my working method, which is one of defining an issue, territory or problem and then planning and developing ways to approach it.

Q. Crisp geometry is a distinctive element of your work and, since the 1980s, you have explored the geometrical possibilities offered by the vessel with forms developed from the circle, cylinder and cone. Can you tell me about the evolution of your ideas through this experimentation? Does this particularly stem from your interest in architectural form?

A. To some extent I rely on defining limits and boundaries to what I undertake and very often these are of a mathematical order, probably stemming from my earlier involvement with pure mathematics and technical drawing. Very often I will define a set of ‘rules’ that then allow for a period of exploration and experimentation which may result in a body of work addressing a single theme through a series of iterative steps.

Q. Your work appears to relate to Minimalism and Conceptualism, but I understand your influences are wide-reaching ranging across medium and time and include inspiration from Classical and Renaissance architecture and 18th century Dutch painting for example. Can you tell me more about the impact of these movements and styles on your practice?

A. I suppose the relationship to Minimalism is the most significant in that it defines an approach to get to the essence of something by removing anything that is unnecessary. Its an approach that tries to explore pure sensation without the encumbrance of meaning. A visit to the Chinati Foundation, established by Donald Judd in Marfa, Texas, was key to my appreciation of these issues. My wider interests in early Renaissance painting, for example, are to do with the optical mechanics of perspective and how the illusion of space might be created on a two-dimensional surface and the strange effects that occur when these don’t quite work. With architecture from the Renaissance its more to do with how a space is physically created through the use of geometry, and how a place is defined. With 18th century Dutch painting, particularly Pieter Saenredam (1597-1665), it’s to do with the creation of these calm empty spaces of church interiors.

Q. Could you me about a regular day in your studio? What are the processes involved in making your work?

A. I’m not sure there is such a thing as a regular day in the studio. Things progress over a period of weeks or months. There will be a period of ‘play’ and experimentation either sketching in 2D on paper or in 3D with whatever materials are appropriate, followed by a period of resolution and planning which may require virtual 3D computer modelling or in the real world with real materials. With work over recent years, molds would need to be made followed by the preparation of clay and then press molding the pieces. These would require several weeks drying before they can be fired, during which time I would probably return to the computer to resolve the two-dimensional aspects of the work and the development of files for the digital printing of the ceramic transfers for the base sections. Once fired pieces require surfaces to be ground flat and polished with diamond abrasives before a second firing at a higher temperature before the application of metal leaf to internal surfaces and final assembly. I also consider reading as a studio activity. Recent areas of research have covered colour theory and recently, the intersection of Renaissance Art and Arab Science.

Q. What is the most challenging element of your practice?

A. its all hard! But I suppose the real challenge is the period of ‘play’, experimentation and reflection at the start of a new body of work. Once a direction is established the rest is sort of problem solving, technical and process development and hard physical labour.

Q. Your work has great breadth ranging from abstract vessel forms to domestic items such as cups and plates to wall-based pieces, often produced in series format. How do you relate these different elements of your practice?

A. I suppose that everything is related in as much as they are all generated by the same mind with the same interests and experiences. However, the overtly domestic ware is separate in as much as it is developed collaboratively with my business partner, Steve Brown, with our company Smith&Brown Ltd and is aimed either towards industry, an individual client or the retail market. Everything else would constitute my own studio practice and although there would appear to be a wide range of forms, they are all driven by the same core interests and concerns. The adoption of a different form will be driven by the establishment of a different set of boundaries to allow one to approach this core from a different direction.

Q. Your ceramics often subvert the expectation of a functioning pot through their formation. Can you discuss this deliberate abstraction of spatial and formal qualities in your ceramic practice?

A. My early interest and introduction to ceramics was through the domestic pot and although the interest in utilitarian function has dropped away the fundamental language of ‘potness’ has defined my practice. This is a language of containment – how a volume is defined and held, how outside and inside surfaces meet, and how a place is occupied. I realised very early on that this was an incredibly rich formal language, one that I wished to become fluent in. I feel that what ever I have produced it has been spoken with this language.

Q. Further to this, elements of your practice convey optical illusionary qualities. Can you talk about your interest in this area of surface illusion?

A. During my time as a student at the RCA I produced a series of bowl forms with cylindrical sides and curved bases that carried a system of white linear marks on their black surfaces that, by chance, seemed to generate a sense of depth. Around this time, I visited the Scrovegni Chapel in Padua with the Giotto fresco cycle on its barrel-vaulted ceiling. Here there is a surface that occupies a real three-dimensional place but on it is depicted the illusion of a totally different three-dimensional world through the early use of linear perspective. In a way it is the ultimate optical illusion. I have returned to explore these phenomena at different times and in different ways, sometimes through the use of geometry, sometimes in more ‘atmospheric’ ways as in a Turner sky and, more recently, through the use of moiré interference patterns, but all the time to give a sense that the space one sees might be of a different order to its physical reality.

Q. You have created vases to be assembled as triptych groups on shelves where the spaces between are as significant as the forms themselves. Can you talk further about this engagement with optics and the negative space in your work?

A. In a way this follows on from the previous question – how space might be given the illusion of substance and how substance might take a back seat. Consider a row of Majolica drug jars with their concave sides, formed so that the apothecary can remove a single jar with ease from a tightly packed shelf. Although the jar and its contents are of real value it is the space between that enables it to be accessed. This series explored some of these concerns with reference to Wedgwood Red and Black figure vases, although through the use of a rigorous geometric language.

Q. Can you talk about the significance of scale in your work?

A. Most of my work has been relatively small in scale – of a domestic order. However, it is possible something quite modest in scale can have a monumental presence through the way it occupies a space – more illusions and more limitations! At times I have felt the need to up the scale and I have done this by occupying the wall, the normal domain of painting and working with a modular approach through the use of repeated smaller modular units e.g. The 270mm diameter dinner plate or the brick sized block.

Q. What is the significance of colour and that of scale in your practice?

A. Colour has always been present in my work but for many of the early years it was the colour of the materials – the black of Raku, the red of Red Earthenware or the reflected colour in platinum leaf. It’s not until later that we get to the use of applied colour and the painterly mark to explore aspects of atmospheric depth illusion. The developing engagement with aspects of minimalism led to a simplification of the pallet. My research into the use of digital print over the last eight or so years has required a much greater understanding of colour theory which underpins all my current work.

Q. You were Professor of Ceramics and Glass at the Royal College of Art for 16 years. What has been the affect of teaching on your practice?

A. I have always taught in parallel to my studio practice and somehow developed a symbiotic relationship between the two where each can enrich the other. It would have been impossible for me to teach with out a vital studio practice. However, the affect of teaching on my practice is more subtle and more difficult to quantify. I suppose clarity of thinking is part of it, as are the development of robust research methods and continual questioning which were central to my approach to teaching also led to my own continual questioning and seeking fresh questions and new answers.

Q. You established the digital print production and consultancy studio Smith&Brown Ltd working with innovative printmaking technologies to develop a distinct vision for ceramic design. Can you tell me more about the projects you are involved with and the particular visual language you employ?

A. The establishment of Smith&Brown Ltd was the result of a major research project I ran at the RCA with Steve Brown. We were aware of developments in digital ceramic laser printing but questioned why so often the results were disappointing. We needed to understand the technology in order to identify where things are going wrong and then develop strategies to overcome or work around them. We conducted this within the context of design for industrial production and the need to satisfy all the legislation to do with heavy metal release and food safety. This we achieved, but the real success was with the development of a new visual language to do with continuous tone (something unachievable through traditional methods), the serial production of unique patterns and the recognition that the economics made possible a new business model for the production of short run, bespoke products. Prior to the pandemic we had been conducting consultancy work for various manufactures, including Wedgwood and Rosenthal. More recently we have been working on the short run production of bespoke designs for an individual client. We are currently in discussion with an American potential partner to develop this side of our activity.

Q. What is the inspiration behind the specific works in the exhibition and how do they sit within the context of your work to date?

A. The core of the body of work for the exhibition have been completed over the past two pandemic years. I see them very much as a continuation and development of my ongoing investigations into contained space, illusion, perception and movement. The works all occupy the wall not the table top, the normal domain of the pot. The wall limits how one can engage with a work. One can approach it head on from a distance or move past it, but you can’t move around it. Formally, they make reference to Donald Judd’s stack pieces and horizontal lines of hollow boxes.

This series titled ’Squaring the Circle’ consist of a line of either square or rectangular blocks of an open yellow coloured earthenware body that has some of the material characteristics of Roman Travertine. Each block contains an elliptical or round space with a flat base that carries a printed moiré interference pattern that gives a sense of movement and phase shift as on moves past the work and colours that change in step with these shifts.

In terms of inspiration, one could quote Donald Judd and much of the music of Steve Reich, particularly the phase works for piano or electric guitar from the 1960s.

Works in the planning stage will make use of arrays of printed bone china plates to explore some of these concerns at a much greater scale.

Q. Who would be in your own ceramics collection?

A. Geert Lapp, a Gordon Baldwin ‘Painting in the form of a Bowl,’ an Etruscan Red and Black Figure vase, Hans Coper, Ron Nagle, A Wedgwood Black Basalt engine turned vase, a ‘Concept’ Tea pot by Martin Hunt for Hornsea Pottery. A set of Eduardo Paolozzi plates for Wedgwood, Takeshi Yasuda, Ken Price etc., etc.

MAKING INTRODUCTIONS: Martin Smith

Release date: Saturday 28 January 2023