John Walker: The Intelligent Hand

By Suzette McAvoy, curator and writer

The landscape thinks itself in me, and I am its consciousness. —Paul Cézanne

The road to John Walker’s studio in Maine runs along the Pemaquid River, emptying into Muscongus Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. Pemaquid in native Abenaki means “situated far out,” and it is one of the oldest English settlements on the Maine coast. For centuries, eels have been fished here from late winter to early summer as they return to the river from the ocean to spawn. This annual ritual is the source of several of Walker’s new works. “Everything you see in the paintings, I’ve seen,” he says. “I’m trying to tell the truth as I see it.”[1]

Central to the compositions of Eel Running, Pemaquid, Pemaquid V, and Pemaquid VI are dramatic, swooping arcs of lines suggestive of the large mesh nets used in capturing the eels. Anchored by bold, patterned buoy shapes, the lines gather energy as they thrust upward, pushing out to the high horizon and the sea beyond. With their geometric crosshatched scaffolding, Resurrection I and Resurrection II intimate the fish ladders that aid the eels on their passage upstream. A favorite Tiepolo painting, The Descent from the Cross, 1772 (Museo del Prado), inspired the titles and compositions. Black Pond and Ripple are concerned with the patterns and movement of water as the tide comes in. Asked about the predominant use of cobalt blue, the artist simply replied, “Joy.”

“I forgot about impressionism, cubism, 20th-century art history, modernism, postmodernism – and saw only the story of his love affair, his liaison, with the visible,” wrote art critic John Berger on seeing the Cézanne exhibition at the Musée du Luxembourg in 2011.[2] My visit to Walker’s studio elicited a similar response. His latest paintings lined the walls, all large-scale, heavily textured canvases awash in lush, vibrant blue. Surrounded by water on the peninsula of land where he lives and works, Walker’s paintings are a testament to his sustained engagement with the visible world, not in the literal sense, but something more primal and poetic.

In this sense, he carries forward the influence of Winslow Homer, who painted his late, consequential seascapes at his home and studio in Prouts Neck, Maine, between 1890 and his death in 1910. Like Walker, Homer spent years studying the seasonal effects of time and tides on his circumscribed patch of coast. In works such as Weatherbeaten, 1894 (Portland Museum of Art), Homer distills nature to its most elemental, pitting the solid form of rocks against the ephemeral motion of the sea. His Prouts Neck seascapes, “balanced on the knife-edge between realism and abstraction,” struck new notes in American painting.[3]

John Marin followed Homer to Maine in the early decades of the 20th century and shared a similar commitment to place. Although he had been painting in various locales along the coast since 1914, Marin spent the last two decades of his life, from 1933 to 1953, at his home in Cape Split. The place, he said, “that lay closer to my heart than any place in the world.” Grounded in observation, Marin’s oil paintings from this period pulse with the energy of his vision in concert with the physicality of his medium. “A copied sea is not real—The artist having seen the sea—gives us his own seas which are real,” he stated.[4] Marin’s assertion of the artist’s reality mirrors Walker’s, “I am not trying to abstract the landscape; I’m trying to make, if anything, realism.”[5]

In the early 1980s, Walker became friendly with artist Richard Diebenkorn. They were both showing at Knoedler Gallery, and they’d go “gallery hopping” when the older artist was in town from California. Diebenkorn was working on his Ocean Park series, which he began in 1967 and continued for over twenty years. Walker had started to paint outdoors, and Diebenkorn was the first to encourage him to show his landscapes. The commonality between the artists is revealed in Walker’s account of his visit to Diebenkorn’s studio in Ocean Park. “I walked down his street and it was like walking through a Richard Diebenkorn painting. When I got to the door and rang the bell, I said to him, ‘You’re just like Courbet, you’re a realist.’ He thought that was wonderful.”[6]

Diebenkorn painted and repainted his canvases, scraping away, reworking areas he thought too precious, leaving evidence of changes until the whole was just right. Walker works and reworks his paintings similarly, although to an even greater physical effect. His surfaces are palimpsests of earlier iterations. Textures range from sheer veils of color to thick accretions of paint and collaged canvas elements. His love affair with his medium, “colored mud,” as he expressively calls it, is palpable. “Touch is very important,” he says, “You have to listen to it. The sound of the brush on the canvas, and a lot of that sound comes through the hand, and the eye sees it, and the heart feels it—at its best.”[7]

The subject of touch comes up often in conversations with Walker. He speaks of looking at a Cézanne, “that tap, tap, tap, of the brush, a multitude of times he touches a painting.”

Rembrandt’s The Jewish Bride, he says, “is the best painting in the world to me, the sublime moment and expression of tenderness, her hand touches his hand.” The communal language among the artists he admires—a widely diverse group including Cézanne, Rembrandt, Constable, Soutine, Goya, Mondrian, Malevich, and the Aboriginal painters he met while teaching in Australia, and others—“It’s not about appearance. It’s certainly about touch. It’s certainly about presentation. It’s certainly about a vision.”[8]

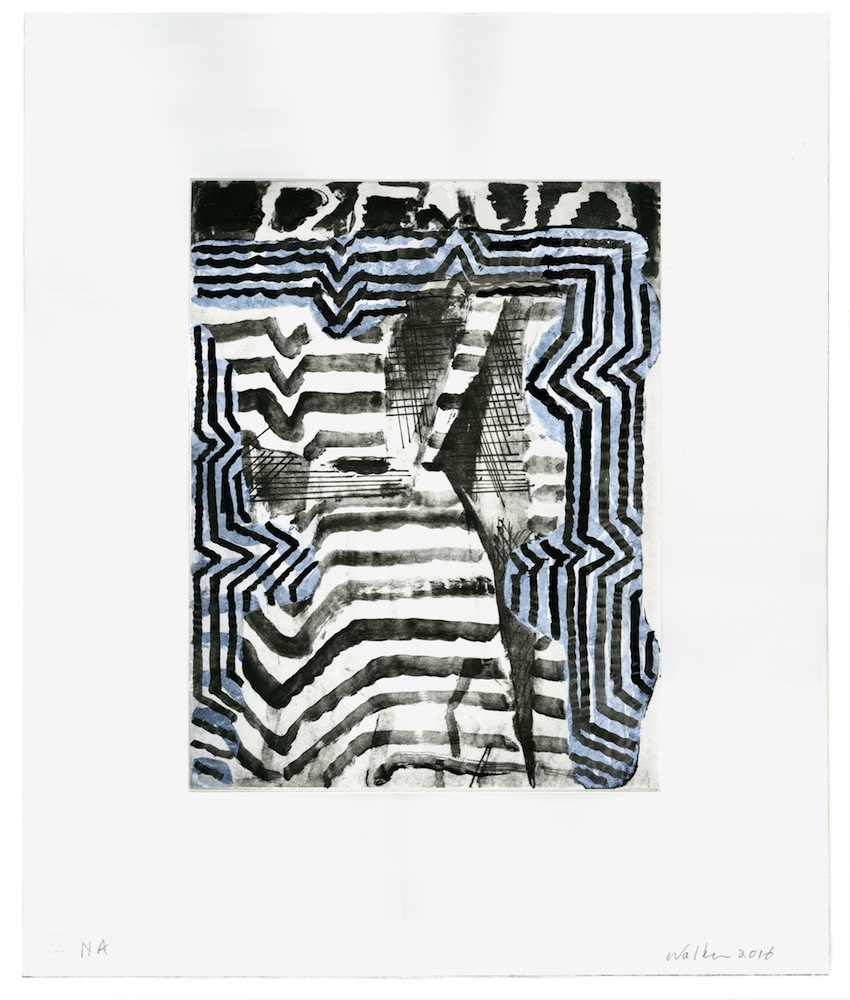

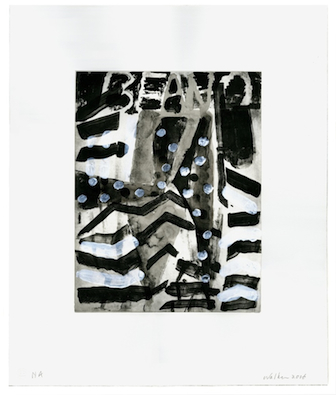

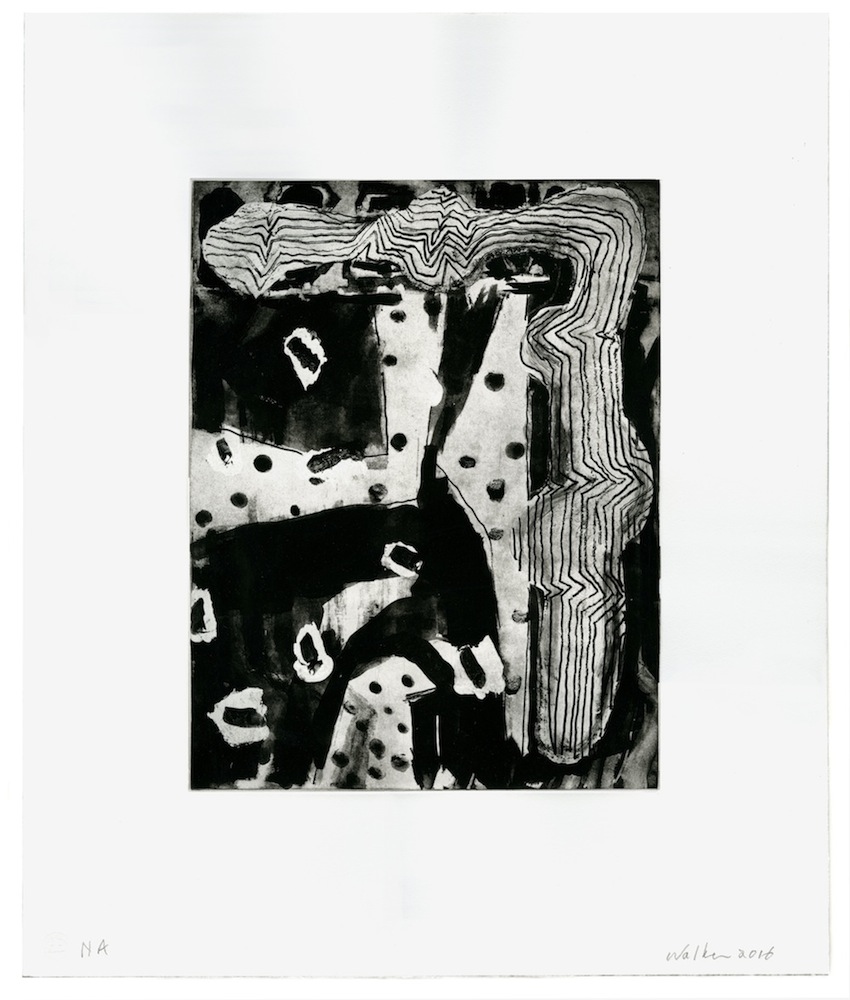

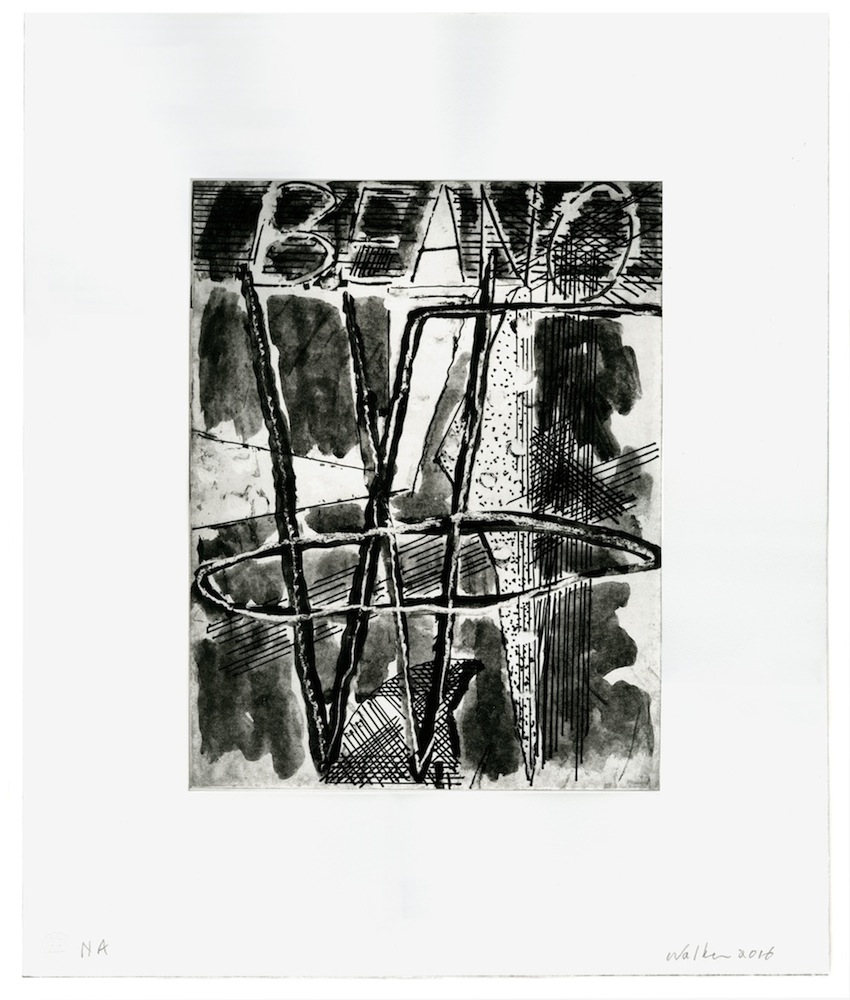

Haptic communication between hand and eye is keenly present in Walker’s drawings, as evidenced in the selection in the current exhibition. “I’ve always felt the most important part of me was my hands, that’s where the intelligence was.” He has drawn continuously since childhood. His classroom teacher’s praise for his drawing of Robin Hood and his Merry Men at age seven—“I had articulated their limbs”—determined him to be an artist. Often he draws obsessively, making hundreds of drawings over days. “Drawing allows you to be extremely personal with yourself; one of its strengths is that,” he shares.[9]

The drawings serve as “idea sheets” and help him solve problems in the paintings he is working on. “Rather than just sitting, looking at a painting, I have to try and draw it as truthfully as I see it.” His favored medium is ink on Japanese rice paper, applied with various soft and stiff brushes. The absorbency of the paper enables the ink to soak through in areas, adding a ghostly richness to the image. Viewing a stack of drawings in the studio, he remarks, “the sound of the paper, it charms me…It’s like I can hear myself breathing.”[10]

Among Walker’s new seascapes, the still-life painting Clock and Shell is an outlier and a compendium of his concerns. It takes inspiration from Cézanne’s The Black Marble Clock, 1869-70 (Private collection), with its florid sensuous seashell and heavy marble clock, its face without hands, arranged on a linen-draped table. In contrast to the solid form in the Cézanne, Walker treats the clock as an outline transparent against the blue ground. It suggests a line from Pablo Neruda’s poem, Ode to Broken Things, “…that clock whose sound was the voice of our lives, the secret thread of our weeks.” Notable is what Walker leaves unsaid, the open edges and spaces between things, allowing for air and light to get in, for anticipation of things yet to come.

Suzette McAvoy is the former chief curator and executive director of the Center for Maine Contemporary Art in Rockland, Maine, where she organized the exhibition John Walker: From Seal Point in 2017.

[1] Unless otherwise noted, all quotes by the artist are from a conversation with the author at his studio in Maine on February 21, 2023.

[2] John Berger, “Cézanne: paint it black,” The Guardian, December 12, 2011.

[3] Bruce Robertson, Reckoning with Winslow Homer: His Late Paintings and Their Influence, published by The Cleveland Museum of Art in cooperation with Indiana University Press, 1990, Chapter Two, p. 25.

[4] John Sacret Young, John Marin: The Edge of Abstraction, catalog essay, Meredith Ward Fine Art, New York, NY, 2006, p. 8.

[5] John Walker in conversation with Jennifer Samet, The Sheldon Art Museum, University of Nebraska, video interview, March 6, 2019.

[6] John Walker in conversation with Erika b Hess, I Like Your Work, podcast, October 1, 2021.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ibid.

[10] The Brooklyn Rail, 64th Weekend Journal, Studio visit with John Walker by Bill Jensen and Margrit Lewczuk, video by Margrit Lewczuk, published November 22, 2020.

John Walker in Conversation with Fiona Gruber

courtesy of Melbourne University

Spending an hour with John Walker is a hugely stimulating experience. As a painter, he’s been part of an international art scene stretching back to the early 1960s; as an educator, his long career has encompassed three continents.

He’s full of anecdotes and opinions about art and artists, and I learn that the painter Mark Rothko once claimed he didn’t think colour important; that in Walker’s opinion Mondrian painted the best evocation of New York in his 1942-3 abstract grid painting Broadway Boogie Woogie; and that terms like abstraction, or abstract expressionism are, to him, a bit meaningless.

There’s a certain amount of arrogance connected with being an artist, he admits. “The idea that you can do it to the exclusion of everything and everyone else.”

But there’s also humility, because it’s only occasionally that you make something really special, he says.

“Over a lifetime of painting you remember ones that you touch somewhere and suddenly it comes back at you. It lights up. It’s a very rare thing.”

He also reveals how he stops painting when he gets bored, but how he’s quite pleased when works return to his studio unsold.

“I love paintings to come back from exhibitions; then I can paint on them again. My dealer will call me and say ‘you know that blue painting? I think I’ve sold it’ and I say ‘no you haven’t, it’s a red one now.’’

John Walker, Caitlin Lee #5, #7, #8 and #9 (2016). Image at columbia.edu. Image courtesy of the artist.

Walker, whom one critic described as “one of the standout abstract painters of the past 50 years,” is 78 and lives in the northerly state of Maine in the USA. Between 1993 and 2013 he was Professor of Art at Boston University School of Visual Arts and Head of its graduate program in painting and sculpture.

Born in England, his connection with Melbourne dates back to the late 70s and he was Dean of the VCA School of Art between 1982 and 1986.

His legacy lives on, not just in the students and faculty members he influenced but in the studio and gallery complex, Gertrude Contemporary, which he kick-started in 1985 and which is still going strong.

So it seems fitting that I meet up with him in the Norma Redpath studio, in inner-city Carlton, where he’s enjoying a month’s stay as artist-in-residence and showing his wife, artist Kayla Mohammadi, around Melbourne.

Redpath, a sculptor, left her workplace and residence to the University of Melbourne; in September 2017, Gertrude Contemporary and VCA, which now manages it, initiated a joint residency for international artists here.

Walker’s sitting in a leafy courtyard at a table dappled with sunlight. Behind him, from the wall outside one of the studios, he’s hung large sheets of paper and, from the look of things, has been busy, with paint and charcoal, on a series of black and white works.

Just as at his American home by the sea in South Bristol, he says he keeps up a daily routine of heading for the studio, reading the papers and then getting down to work.

“If you’re not there it ain’t gonna happen,” he states matter-of-factly, in a voice that still bears strong traces of the English Midlands and the city of Birmingham where he grew up in the 1940s and 50s.

At both the VCA and at Boston he kept a studio in the art school and the door was always open to students. It was part of a larger philosophy of engagement and seemed only fair he says.

“If I could walk into their studios any time of day or night, I thought they should have that privilege with me.”

One of the lessons he hoped they’d learn, he explains, is that an artist paints a lot of dud work and that failure is a vital part of the journey.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

“At the VCA it was important that students should see someone who’s a so-called professional and how they go about making their art and the sheer amount of art they make … there should be the expectation of a lot of failed art which is good for them, because if they try and make a finished work every time they’re going to be a very bad artist.”

There seems to be a general consensus in the art world that Walker is a very good artist.

In 1985 he was a finalist for the Turner Prize; more recently, at the Yale Centre for British Art he was included in its 2010 exhibition “The Independent Eye: Contemporary British Art from the Collection of Samuel and Gabrielle Lurie” in a select group of post-WWII painting luminaries including Patrick Caulfield, Howard Hodgkin, John Hoyland, R. B. Kitaj and Ian Stephenson.

But success came early for Walker and he’d had his first solo show at London’s Hayward Gallery by the time he was 29, in 1968. As he puts it drily, he was “exhibiting with the big boys and girls.”

By the 1980s he was one of Britain’s most successful mid-career artists, with solo shows across Europe and the US including at the Hamburg Kunstverein in 1973 and the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1974.

Sandwiched between those exhibitions, he’d also represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1972.

His painting career wasn’t the primary reason the VCA was keen to recruit Walker however; he’d also taught at some of the top schools in London and New York and been a visiting Professor at Yale University’s new Graduate School of Art and Architecture at New Haven.

It was in 1977 that his association with Australia began, with the Powell Street Gallery. Its dynamic co-director David Rosenthal, who was also a medic, had seen his work in New York and arranged for some to be shown at the South Yarra space.

Walker had also got to know the art historian Patrick McCaughey when they were both Harkness fellows in New York in the early 1970s. McCaughey went on to become the first professor of Fine Arts at Monash University in 1972. They kept in touch and in 1979 McCaughey offered him a Monash residency.

It was there that he had met his future wife, academic and art critic Memory Holloway. An artist’s residency at Prahran College of Advanced Education was arranged for the following year and the scene was set for a more permanent move to Australia. He says he left the UK gladly, although he knew he was waving goodbye to the British art world: “Basically it was the end of my career in England. The English, if you don’t let them love you they don’t like you anymore.”

Walker’s appointment to the post of Dean was a breath of fresh air says VCA’s current Head of Art, Jan Murray. “He was generous and encouraging,” she says, and “had a quiet authority that came from his international achievements…he had nothing to prove. He shifted the culture and once done it couldn’t be reversed.”

Walker says that his aim was to raise the bar higher.

John Walker, Walker Form with Yellow Shield (1986-87). Reproduced courtesy of the artist.

“I taught at Yale and the Royal College and they were like the elite institutions, and I was told that the VCA was an elite institution so I didn’t think there’d be any difference and in many ways there wasn’t, but I did feel that the expectations for students and to a degree the faculty wasn’t as professional as it was, say, at Yale.”

Norbert Loeffler, Lecturer in Critical and Theoretical Studies and one of the VCA’s longest-serving staff members, is less circumspect; he says that by the time Walker came to Melbourne, the city had several art schools and the number of students and professional artists had also grown considerably. The VCA was not doing well, he says, and Walker brought a much-needed dynamism and educational rigour to the college, which at that stage offered scant teaching of theory or history.

“In the late 70s and early 80s [the VCA] had started to drift and there was no compelling energy,” says Loeffler. “He was the ideal person; he came, saw it and said ‘we’re running specific classes, regular tutorials and a proper art theory and history program … we went from one class per week to 11 in one year.”

Walker says that although some faculty members were initially critical of his appointment – “people who didn’t want an Englishman running the school” – his approach combined appointing young teaching staff for energy (many young sessional teachers were brought in including Jan Murray, Howard Arkley, Bill Henson and Phil Hunter) and older ones for wisdom, and the “work hard party hard” approach won opponents over.

“[They] eventually came to the party because they could see the students were having a great time and they were learning so much,” he says.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

He also wanted to break the idea that the best art was being made elsewhere.

“When I started here, people used to look at me incredulously when I said ‘you don’t have to go anywhere’.”

One of Walker’s lasting legacies was setting up Gertrude Contemporary in 1985. Then known as 200 Gertrude Street, the combined studio and gallery complex in Fitzroy was a first for Australia.

The former textiles factory had been offered to the Victorian Council for the Arts (as it was then called) and Walker brokered a deal for a year’s rent with the building’s owner, Philip Cormie, which included one of his paintings and $10,000 of his own money.

Of his beneficence, he says: “If nice things happen to you, you should give back, and people had been terribly generous to me.”

The complex was a response to the isolation experienced by artists post-college, says Walker.

“I was concerned that my graduate students were not being supported once they left school,” he says. The deal, explains Walker, was that it was open to all art school graduates, not just those from VCA; that each artist had to pay for power and that they couldn’t stay for more than two years.

The first director of the exhibition space was Louise Neri, currently a director of the international Gagosian Galleries.

After getting the ball rolling, he then left it for others to run, including his then-wife, Holloway, who was co-chair.

Murray, who had one of the first residencies, said the Gertrude Street complex reflected Walker’s knowledge of similar ventures overseas, including the collective PS 1 in New York.

Its exhibitions soon became a magnet, she says, in an era before the explosion of artist run initiatives in the 1990s.

“He supplied a destination and it was ecumenical. We needed a network and a community and it was pretty amazing in terms of the vision John lent and the generational focus it gave. A lot came out of it.”

Earlier this year, Gertrude Contemporary left its inner-city premises and has relocated to Preston. It maintains its two-year studio residencies and has stuck with 16 of them, as in the original building. Mark Feary, its current director, says it’s still unique in an Australian context.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

“Having a community of artists forms deep connections between them … it’s always done very well as it fights against hermetic practices,” he says. The new space might lack the grungy charm of the former, he adds “but it’s taken its history with it and for the first time we’ve been able to architecturally develop the spaces.”

Walker is keen on things developing, and against organisations becoming too bureaucratic. He’s glad that Gertrude Contemporary has moved on.

His time in Australia sparked new ideas; the paintings and drawings he did here include his Oceania series and his Prahran Etchings as he soaked up Australian and regional cultural influences. And he’s continued to exhibit here too, with a show at Tim Olsen Gallery, Sydney, in 2012.

He muses on the difference between the art he did as a young man and the art he’s making now. Is he a better painter? I ask.

“Different. One of the things I’d tell my students is ‘you can’t paint an old man’s painting. You can paint a 21-year-old’s painting and I can’t paint a 21-year-old’s painting, only an old man’s one. But a masterpiece is equally available to both of us.’”

And although he cautioned his students that many artists commit themselves to “a very lonely life, mostly in a room on your own” he says that if you dedicate yourself wholeheartedly there’s nothing better.

“Look what it gets you if you really do it; it gives you a wonderful life. I feel blessed.”

By Fiona Gruber

An essay and interview by Colin Smith, Associate Editor of Turps Banana Painting Magazine.

Revisited and edited March 2019

A friend who works with Sculpture and Installation said to me recently “The problem with Painting is that it has too much history”. My instantaneous reply was “That’s one of the very things that I most like about it.” I’m fairly confident John Walker’s answer would have been similar.

My first encounter with him as a student at the Royal College of Art in the late 1970s was not necessarily an easy one. His work was extraordinarily prominent and highly thought of at that time and there was barely a student who was not making pastiches of his work. I was one of the few who was not but when he saw what I was trying to do he was characteristically perceptive, helpful and sympathetic. Later he was instrumental in helping me get a Harkness Fellowship to Yale, and we still meet up from time to time.

It has always struck me as profoundly unjust that over the decades since he moved away from the UK, sometime around the mid-1980s, his work once so prominent should have vanished from sight along with him, and that a large number of younger artists were completely unaware of his practice. His work now seems as relevant as ever and about ten years ago, with the backing of Turps Banana Painting Magazine, I flew off to Boston to interview him and to try and set that situation right.

John’s reputation in the USA, where he has been living for some time now, is securely established and unquestioned. His involvement with the dilemmas of illusion and surface have always been paramount. Film critics often reference the emotional agency of depicted space in movies, seldom referenced in that way by commentators on the plastic arts. Space, or the illusion of it, has always been prominent in John’s practice and to my mind is much more relevant than the introduction of ‘namable’ subject matter or even text. The Door is perhaps a more fitting metaphor for John’s paintings than The Window, and the subject matter or text could be seen only as a possible key, nothing more, nothing less. Complexity or contradiction has never really been problematic for the poetic imagination. As the art world seems to be devolving into part of the entertainment industry, these works vastly repay any effort demanded to understand them, their context and background. This new and exciting exhibition of John’s work is long overdue.

Here follows an updated version of my interview with John, which despite some years having passed still offers many insights.

CS: One clear trait of you practice is a determination to apply the paint in varied and unexpected ways.

JW: I’ve always been interested in what you may call talking with the brush - that’s something inherent in great painting. The way the artist kind of talks himself through a space or a distinctive form. It was one of the things that worried me about a lot of my friends’ paintings, Minimalists if you like, this throwing-out of the language of the brush. It was there in the paintings I admired, that distinctive touch which you see in a Chardin for example and which makes you gasp when you see the beauty of it.

CS: Could it be said that your attention was moving away from just the act of painting, towards referencing things outside of that?

JW: Well, that’s true to an extent. I’d come to feel with the ‘collage paintings’ that they were solid enough to feel – if you hit one for example, you’d break your hand. But I suppose what I’d reverted to was that it was no longer just about force because I’d always believed the same of say a Vermeer painting that if it fell on you it could kill you because it’s so finitely structured. There’s a dialogue going on all the time and even though I thought the collage paintings were going well what was missing in the paintings was ‘going back to air’ – how do you paint air? I was beginning to feel I’m not doing the things I care about. I was looking at Rembrandt’s portraits for example – how do you paint the space around a form?

CS: Would it be fair to say that in the past you were interested in the ‘whole painting’ as an image, whereas now you are becoming more interested in an image ‘within’ the work?

JW: To an extent it was: “how can I find a form which I can place with air around it?”

CS: I seem to remember reading years ago that you’d quoted Picasso saying that he wanted his paintings to stop just this side of abstraction and that you wanted your paintings to stop just this side of figuration.

JW: One of the most inspiring things I ever read was by Malevich, who, when asked what his ambition was, said to imbue a square with feeling. Somehow that square had to act figuratively – not abstractly, even though it was an abstract form. It’s the same with Rothko – you’re not just seeing a rectangle, those forms somehow act figuratively on you. Someone who doesn’t do it so well is Barnett Newman. If he hadn’t called those paintings Stations Of The Cross they would just be black and white paintings.

CS: Some of the dialogues, which have unfolded in your work over the years have an affinity with Guston – the reintroduction of ‘nameable’ imagery for example. He seemed to have had a road to Damascus conversion, whereas your developments seem to have evolved more slowly.

JW: It’s very much a narrative thing – there’s a lot of narration in Guston. Even though I met him several times it’s quite hard to talk about him. The language or the ‘touch’ of paint is always the most important, and some times the subject matter is just a kind of filler.

CS: Would you agree that the forms in your work are usually defined by the edges of shapes rather than by the brush marks modeling them? The marks seem more to animate the shapes rather than model them?

JW: I spend a lot of time trying to work out where things meet – where form meets space. I spend a lot of time trying to activate that area. That’s where drawing is. I love looking at Albers – the precision of where the colours meet creates drawing.

CS: Let’s talk about the way you have represented space in your paintings. Very often the forms or planes lie parallel to the picture surface.

JW: Everyone seems to have his or her own definition of what the picture plane is. I suppose I wanted to place the forms in front of the picture plane. I am thinking of one particular Cezanne self-portrait, where he established the picture plane very early on in an area just behind the ear, then, later on, everything else has a discussion with that part. There is a kind of building in and out of the picture plane. The painting in the Phillips Collection in Washington seems to exist in the space between you and the surface. The painting is about four feet away but Cezanne is only about two and a half feet away.

CS: I suppose what I mean is, in say the Alba paintings, the forms and the areas around them are upright as opposed to your paintings, which have a recessive sloping surface. From my own experience I know it is easier to get the marks to lie down and fuse with the forms when they are parallel.

JW: Well, that’s the problem with landscape painting – you find that things move away from you pretty quickly. The thing is you are always making a painting. There’s a physical difference between what is a ‘view’ and a ‘painting’. Most of those paintings were actually started outside in the landscape, then when I had something there I brought them in and had a dialogue with the work, then took them out again and to see if they ‘fitted’, to see if they were then actually part of the landscape. They don’t have to look like it.

CS: Are they based on a specific area?

JW: Very much so. I’ve been going up to this area, where I have a studio in Maine, over many years, and it really happened about the time I had a breakdown and I didn’t really know where I was going. I found this cove where all the shit came in out of the ocean. When the tide went there was all this mud and it fitted into a group of paintings where mud was the central theme – homage pictures to my father who fought in the First World War. It took a long time but I suppose what I wanted was for people to be able to say I knew more about this spot than anyone else in the world. Cezanne knew more about Mont Sainte-Victoire than anyone else, and I‘ve got my little piece of mud! It changes all the time, every time the tide rolls in or out.

CS: It coincided with a difficult period in your life?

JW: Yes, there was a period of about eighteen months when I just could not work. The landscape refreshed me and helped me to come back.

CS: Tell me about the introduction of text into the paintings.

JW: It came at first from a drawing my daughter had made of a birthday card which included the text For You, and then I made a big painting, which I still think well of, with those words on it. Then it grew a little bit and there’s a whole series of paintings somewhere of birthday cards.

CS: That relates to you not wanting to exclude anything from paintings.

JW: Yes, I just don’t want those rules.

CS: I’ve found a quote from way back that says, more or less, you don’t like maximum impact paintings, but prefer ones that reveal themselves more slowly. What was the context for that?

JW: That’s a really early statement, from when I was a very young man. There was a time when, for a while, I found my art being exhibited alongside Warhol and Lichtenstein – all that wham-bam stuff. I felt my work was really not about the same thing at all, which in some sense forced me into a kind of retreat.

CS: What about Drawing and printmaking – you’ve done a lot of both. How do they fit in with the painting?

JW: Usually when I draw its to check the painting out. I don’t want to just rely on my eye and an immediate response - I want to try to visualise more, to internalise. To see how accurate the painting is. Did I really achieve the placing of forms I intended? I see the drawing as a confirmation, mostly after the painting. I found myself going out with watercolours into the landscape. I don’t need a camera. I want to feel I can paint anything. To me that’s one of the definitions of what a good artist is. Everything is available.

John Walker – Perception in Paint

by Dr Claudia Milburn, director of programming

written in February 2023.

John Walker’s dynamic ‘Blue Series’, a sequence of electric, large-scale paintings, all created in 2022, are testament to an artist who, now in his ninth decade, is working with a spirit and confidence accrued through a lifetime invested in exploratory endeavour. Walker had long held the ambition to create a body of blue paintings and, finally, the eight or nine buckets of blue paint which had been sitting in his studio for a decade, have found their way to the surface of the canvas. Typical of the artist, these works are therefore the result of considerable rumination. They are also finite, with the paint gone, Walker will move on.

Pictorial and pattern motifs echo throughout Walker’s oeuvre and this Blue Series is no exception. Sinuous lines, geometric patterns, repeating shapes, families of flattened forms – each unique but with shared characteristics – run through, creating a body of work brimming with vitality that invigorates the eye and livens the imagination. They are, to my mind, the summation of an artist who has interrogated the canvas over years of questioning, driven by the belief that “The painting is only any good when it’s presence is greater than I am.”[1]

In Pemaquid V, Pemaquid VII and Eel Running Pemaquid swathes of undulating waves traverse the canvas from opposite sides, colliding and merging centrally to create a dynamic meeting point while other shapes, rhythms and patterns dance across the surface. The paintings are dominated by the juxtaposition of two principal colours – a cobalt blue hue and a bright white. While other colours feature, notably shades of sienna, ochre and accents of jade in some of the works, it is the striking combination of blue and white which characterises the series. This colour coalescence, together with the fresh luminosity in the surface quality of the paint, brings to mind ancient Qinghua porcelain with its cobalt oxide pigment and translucent glaze. In Ripple II the blue and white oblique stripes zig-zag across the canvas, while in Resurrection I and II, a patchwork of horizontal and vertical lines criss-cross over areas of blocked colour with a textural quality reminiscent of basket-weave. In each case, the dominant patterns dynamically divide the picture plane. Walker’s mark-making is free, vigorous and direct; the paintings are immersive, enigmatic and atmospheric. It seems impossible not to respond to the all-consuming power and impact of the work.

A sense of place and the essential spirit of that place – the genius loci – are fundamental factors in Walker’s oeuvre. His life and career have taken him across continents to many different locations which have regularly provided core subjects for his work. In recent decades it has been his home territory in and around Seal Point in Maine, USA, that has provided the stimulus, this marine landscape inspiring countless canvases. It was, however, many years before he could use this location as subject matter, its scenic beauty had initially seemed too intense and overwhelming. This place had thus been absorbed and assimilated in his mind, time and time again, before it became a possibility to put brush to canvas. Located at the tip of the peninsula, Seal Point provides a unique panoramic landscape view of this part of the Atlantic coastline offering the ideas and impetus for Walker with the elemental drama of land, sea and sky. The ‘Pemaquid’ works relate to the picturesque peninsula in Maine, one of the region’s seven geographic ‘fingers’ close to the artist’s home. ‘Pemaquid’ is an Abenaki Indian term meaning ‘situated far out’ and representative of this coastal point, lying at the ocean’s edge. Tidal mud flats quilted with patterns of waves generated from the rhythms of the sea, currents of water rushing over the mud, rocky strata delineating the foreshore, reflections in the residual pools as light shimmers over – these are just some of the elements that characterise this inspiring location. It is a place in a constant state of flux forever animated by nature’s atmospheric conditions – shifting weather, time of day and the seasons. Walker is in tune with its sounds, shapes and sensations, its textures, colours and movement. These are the ingredients of his paintings, and it is his internalisation of these components, viewed at different times in different conditions, that coalesce on the canvas surface as a series of expressive shapes and forms. Moments and memories built over years permeate the works. All that enters the picture plane, every shape and gesture, has been absorbed by the artist over time, and his vision translated onto the surface of the work. These are not paintings with the intention to abstract, but moreover, to represent the veracity of the scene as witnessed and understood. They are emotive responses to his visual senses and his aim is to realise his impressions, to reflect a semblance true to his perception. In this way he is searching for the essence – a true Modernist in search for the fundamentals and authentic in his resolve. He believes in the power of painting to explore this quest and to investigate what it is ultimately possible for the medium to achieve. While Walker aims to know and understand this specific landscape around Seal Point like no other, the aspiration is always for the painting to take command, to tell him something he did not know before, to take him somewhere he has never been, and thus indicate a power of presence that has the ability to communicate truth, a higher state of reality.

The crescendo of sound created through the impact of Walker’s work has reverberated for generations. A prolific painter, he has continually confronted the issues that have plagued many artists in the second half of the 20th century and into the 21st and has faced up to the challenges posed by abstraction. In so doing, Walker has contributed to a significant narrative on Abstract Art and created a dialogue that has allowed for others to take heed and respond to the language of his work and its ability to communicate with such expressive potency. Walker represented Britain at the Venice Biennale of 1972 and has since taught across continents – in art schools in England including the Royal College of Art, at Yale University, during the 1980s as Dean of Victoria College of Art in Melbourne, Australia and, in more recent decades (from 1993 to 2015) at Boston University, Massachusetts, thus his influence on generations of artists has been far-reaching.

Walker’s first recognition of the potency of abstract art was in 1959 at the Tate Gallery’s exhibition The New American Painting where he encountered a work by Jackson Pollock entitled Number 12 that had a profound effect. Abstract Expressionism bore witness to a freedom of expression and a vitality of approach that was spontaneous and direct. For Walker, it was a visceral response – physical, honest and real. Urgent brushstrokes or paint liberally poured onto the canvas, colour interactions across the surface, a sense of active space, tensions in pictorial depth, the push and pull of forms, all evidencing pure unhindered expression. These works strongly resonated with Walker and fuelled a lifetime of exploration into the potential of painting as a medium to offer an impassioned language of authenticity. He comments, “When you paint something it has got to be perfectly honest and perfectly truthful. And that’s the only way. And that’s what New York has taught me.”[2]

Walker’s impact and his importance, stems partly from his constant innovation, he has been ceaseless in his quest, never settling, always charging forward, each time with renewed vigour and conviction, motivated by the mission of the work. As writer and critic Dore Ashton described in the introduction to Walker’s exhibition at the Hayward Gallery in 1985, he “works with the exuberance of a tinkerer or with the solemnity of an old master.”[3] He has long been preoccupied by shape, questioning its impact and significance. Through his work, he has persistently embraced the possibilities of form and considered how it is possible to truly imbue such form with meaning. As he expressed in 1972, “But if I was going to make non-objective art, the shapes I was going to use would have to have dignity, if you like. They would have to have a presence, always, which made them a sort of phenomenon. They conveyed feelings. They could not just be a red shade next to a black shade.”[4] In this, Malevich offered a touchstone to Walker, “One of the most inspiring things I ever read was by Malevich who, when asked what his ambition was, said to imbue a square with feeling. Somehow that square had to act figuratively – not abstractly, even though it was an abstract form.”[5] This, he realised, was the same mission undertaken by Rembrandt, to convey human emotion through the parameters of a pictorial image, and it was the recognition of this parallel that enabled the door to open into the potentiality of abstraction.

For shape to have substance and the composition of elements to have true merit, Walker has embraced a journey which has barely left a page unturned in the history of art. References to the European masters Rembrandt, Vermeer, Velazquez, Goya, Manet, Matisse and Picasso, among others have infiltrated the work. Walker comments “I am a painter, and I respond”[6] acknowledging the importance of this dialogue with the art of the past to provide the core building blocks to channel his direction in the present.

In his ‘Labyrinth’ series of the late 1970s and early 1980s Walker pays homage to Velazquez’s Las Meninas (1656) evidently relating to the multi-layered depths, interrogation of pictorial space and compositional drama in the iconic painting. A similar level of inspiration can be traced to Vermeer. Walker has referenced Vermeer’s View of Delft (c.1659-61) as an image that endures with him, no doubt influenced by the clarity of detail and gleaming richness of paint, comparable to the compelling diffused light and luminosity of intimate portraits within his interior studies. Walker has long been deeply affected by the intense pictorial language of Goya who he has described as his enduring hero, omnipresent in his mind and who has reduced him to tears on seeing his work in the Prado.Goya’s virtuosity of composition and the emotional, psychological drama of his paintings evidently resonate on a level that has penetrated Walker’s psyche and impacted his own approach.

Walker’s interrogation of the picture plane owes debt to the visual and structural analysis of Cubism and the possibilities opened by Picasso and Braque for their spatial invention and interpretation of form. Equally, Walker finds a close affinity with Matisse in a shared visual dialogue. The compression of depth and flattening of form, moving to the use of linear rhythms, colour interactions, evocative distortion of shape and composition as depicted by Matisse clearly struck a chord with Walker in his search to realise his own vision of the subject experienced. Walker, like Matisse, tenaciously pursues an idea in a process of interrogation and reconfiguration until achieving something close to the semblance of his perception, probing the very essence of painting. Matisse describes, “For me nature is always present. As in love, all depends on what the artist unconsciously projects on everything he sees. It is the quality of that projection, rather than the presence of a living person, that gives the artist’s vision of life.”[7] This same sentiment can be seen observed in Walker’s uncompromising determination to achieve his aim.

Integral to Walker’s practice, and his ability to gain proximity to the essence of his subject, is the process of drawing. For him, drawing is the essential lifeblood, the connection between heart, hand and mind. He draws daily to enable him to look, to think and to feel. Drawing enables him to examine and to understand, to deconstruct and reconfigure in order to get beneath the surface and reveal the essence. Walker’s engagement with drawing is revealing of what, for him, drives the creation of the work. His drawings are never preparatory, in fact, quite the opposite. He frequently draws from his paintings in a process of assimilation and questioning, a way to assess whether his paintings have achieved that which he is striving to convey. From drawing to painting back to drawing, he works assiduously until the image that he arrives at has this necessary vitality, as he describes, “I’m interested in what the painting has become not its intention. If the painting is going well it creates its own representation, its own reality so then I’m totally convinced it is reality.”[8] For Walker, one work leads into the next and then the next in a pursuit of perpetual discovery. It brings to mind the first line from T. S. Eliot’s poem ‘East Coker’ from the Four Quarters, “In my beginning is my end.”[9] The great gift of Walker’s work is in its presence, a result of his steadfast resolve and his belief in the transcendental power of painting.

© Dr Claudia Milburn, February 2023

[1] John Walker, Interview with Bowdoin College, 2017

[2] John Walker, “John Walker on his painting,” Studio International, June 1972, 244

[3] Dore Ashton, “Introduction”, John Walker, Hayward Gallery catalogue, 1985, 5

[4] John Walker, “John Walker on his painting,” Studio International, June 1972, 245

[5] John Walker, Interview with Colin Smith, associate editor of Turps Banana in Paintings, Prints and Works on Paper 2008-2018, Messums Wiltshire

[6] John Walker, “John Walker on his painting,” Studio International, June 1972, 244

[7] Matisse – In Raymond Escholier, Matisse ce vivant. Paris, 1956. Translation: Matisse from the Life, London 1960.

[8] John Walker, Interview with Bowdoin College, 2017

[9] T. S. Eliot, ‘East Coker’ in the Four Quartets, (London: Faber and Faber, 1944).

A painter of consciousness, of consciousness in the world, as it goes by

by Jonathan Watkins, curator, writer and former director of Ikon Gallery, Birmingham

written in 2023.

In the middle of the Midlands, Birmingham is the English city furthest from the sea, too far and yet not far enough away from London. Born in the first year of the second world war, John Walker grew up there during a time of unprecedented social upheaval. The son of working class parents, he witnessed the final fling of the manufacturing industries that had expanded Birmingham rapidly in the nineteenth century

Walker graduated from a local art college into a society that was caught between the promise of a brave new world – “forged in the white heat of technology” – and the legacy of an international trauma: modern shopping centres and motorways on one hand, gaping bomb sites on the other. David Prentice, a contemporary, describes how Birmingham was for artists in those days: “We agreed that [it] was appalling, not facing up at all to current issues in the art world and so on. It is very difficult to describe really how deprived Birmingham was in those days. It was a glum little city. We loved it as students because it had secret pockets of things you could find out … but it took bloody ages!”[1]

John Walker’s star rose quickly. Appreciated by teachers and peers for his exceptional talent, he was very driven but not always on the right side of the local arts establishment. This led to a split between him and the college, where he had started teaching, and a move to Blackwell, a village outside Birmingham. The story he then tells is like a leaf taken from Vasari’s Lives of the Artists:

… one day this woman came up the stairs. She said she was visiting someone in the village, and was told that an artist lived here, and would I mind if she had a look around? I was painting these big paintings, at least 20-feet wide. There were thirty of forty paintings that size, and we went through them. She sat down, I gave her some tea, and she said, “Have you ever thought of showing in New York?” And I said, “No, of course not.” She said, “Would you like to? We could show them in my gallery.” It was Betty Parsons. We became very good friends. So I had a show with her in 1967.[2]

Then followed a Harkness Fellowship, enabling Walker to spend more time in New York, and in 1972, while living in London, he was chosen to represent Britain at the Venice Biennale. An extraordinary achievement. In the same year he accepted an invitation to be the solo artist for Ikon Gallery’s inaugural exhibition at its new premises in the Birmingham Shopping Centre – poignantly located between a Habitat store, promoting a cool modern lifestyle, and an army recruitment office. A coup for Ikon, the show comprised chalk drawings made directly onto the gallery walls, a rare (and brave) diversion from painting on canvas that gives it legendary status in local art history. According to Ikon’s then director, Simon Chapman, it was “astonishing”.[3]

* * *

Forty-five years later, I was the director of Ikon when I met John Walker for the first time. I saw the catalogue for his most recent New York exhibition and was similarly impressed by images of the new paintings. His eightieth birthday was imminent and it quickly dawned on me that another solo show at Ikon was long overdue, this time to celebrate the achievement of an artist, Birmingham born and raised, who was continuing to go from strength to strength. I wrote to him asking if he was interested, he said yes and we arranged a studio visit.

And so to Maine. New England. With old England long since behind him, John had spent intervening years in Australia before returning to the US, teaching in Boston while setting up a family home and studios in and around New Bristol, looking out onto the Atlantic. Where he now lives and works is a far cry from where he grew up.

On arrival one is immediately struck by the elemental nature of the place, the sea, the big sky and a landscape that is at once tough and picturesque. More weather than English drizzle. John is a good guide, driving along coast roads in his pickup, stopping off at favourite cafes and diners on the way to locations of particular interest, some of which have inspired him to paint. One such he has renamed “Shitty Cove”. He explains, “I can’t paint the scenic part. I’m anti-scenic. It took me about ten years before I could paint the place, even though I was living there. I found a place where it smells, and all the garbage comes in and that allowed me to paint because it wasn’t scenic.”[4]

During studio visits we concentrated on paintings that might be included in the Ikon exhibition. Characteristically they flirt with the line drawn between abstraction and figuration, but with a formal clarity and colour that is quite unlike an earlier deliberate muddiness. John’s use of striation to suggest waves and tides is visually compelling – in a Aboriginal kind of way – and the occasional repetition of stylised fish motifs fits in with an aesthetic strategy that has served him well throughout his artistic career, but now it is smartly “dumb”, less arcane, more obviously about a here and now. This is work that has an edgy beauty that is as refreshing as it is confronting. It keeps us on our toes.

This was the key to the success of John’s exhibition at Ikon, the reason why it not only attracted visitors of his generation, but also appealed to younger artists, especially those who, like him, prioritise the formal inventiveness that paint affords. When he says, “It is the height of ambition, it seems to me, to be a painter”, it is not about the fetishisation of the medium, or art for art’s sake, but rather an aspiration to the condition of free-verse poetry.

This last thought occurred to me and then I remembered that John was a good friend of William Corbett, a poet at the heart of literary life in Boston. In the catalogue for our Ikon exhibition, we published a poem by him, dedicated to John, and the transcript of a lecture he gave on John’s work at the New York Studio School shortly before Corbett’s death in 2018. The lecture is especially touching, referring to time the two men spent together while teaching at Boston University: “I loved working with him, saying what I, a poet who loved painting, could get away with saying. Loved the gossipy hours over wine after crits with the painters. Talking for five or six hours unwinding … More laughter than yackety yack.”[5] The admiration was mutual, and each clearly identified with the other. In an interview some years previously, Corbett described himself as “a poet of consciousness, of consciousness in the world, as it goes by.”[6] The same could be said for John Walker, painter.

Such sensibility and unpretentiousness are rare in the art world. Gossipy hours over wine after long days of installation, unwinding, more laughter than yacketty yack, it was a privilege having him back in Birmingham.

[1] David Prentice, interview in Some of the Best Things in Life Happen Accidentally, exhibition catalogue, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham 2004, p.117

[2] Jennifer Samet, ‘Beer with a Painter: John Walker’, Hyperallergic, 18 May 2013

[3] Simon Chapman, ‘Welcome to Ikon’, This could happen to you, exhibition catalogue, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham 2010, p.132

[4] Jennifer Samet, Op, cit.

[5] William Corbett, ‘John Walker Drawing’, John Walker. New Paintings, exhibition catalogue, Ikon Gallery, Birmingham 2019, p.14

[6] ‘The Romance of Life and Art: An Interview with William Corbett’, Rain Taxi Review of Books, Spring 2005