John Walker in Conversation with Fiona Gruber

courtesy of Melbourne University

Spending an hour with John Walker is a hugely stimulating experience. As a painter, he’s been part of an international art scene stretching back to the early 1960s; as an educator, his long career has encompassed three continents.

He’s full of anecdotes and opinions about art and artists, and I learn that the painter Mark Rothko once claimed he didn’t think colour important; that in Walker’s opinion Mondrian painted the best evocation of New York in his 1942-3 abstract grid painting Broadway Boogie Woogie; and that terms like abstraction, or abstract expressionism are, to him, a bit meaningless.

There’s a certain amount of arrogance connected with being an artist, he admits. “The idea that you can do it to the exclusion of everything and everyone else.”

But there’s also humility, because it’s only occasionally that you make something really special, he says.

“Over a lifetime of painting you remember ones that you touch somewhere and suddenly it comes back at you. It lights up. It’s a very rare thing.”

He also reveals how he stops painting when he gets bored, but how he’s quite pleased when works return to his studio unsold.

“I love paintings to come back from exhibitions; then I can paint on them again. My dealer will call me and say ‘you know that blue painting? I think I’ve sold it’ and I say ‘no you haven’t, it’s a red one now.’’

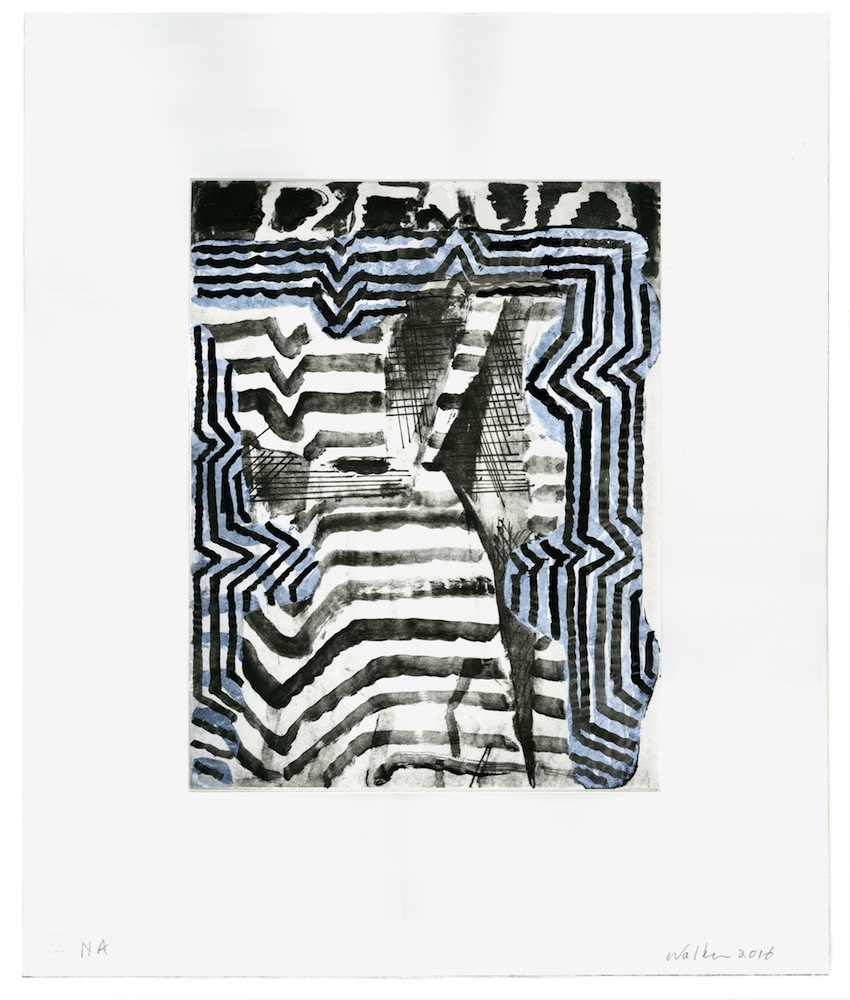

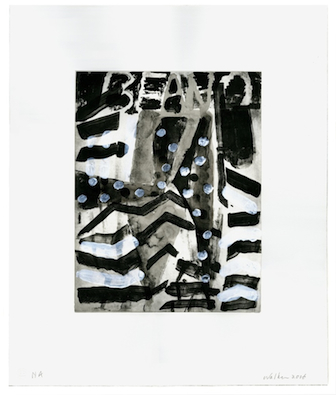

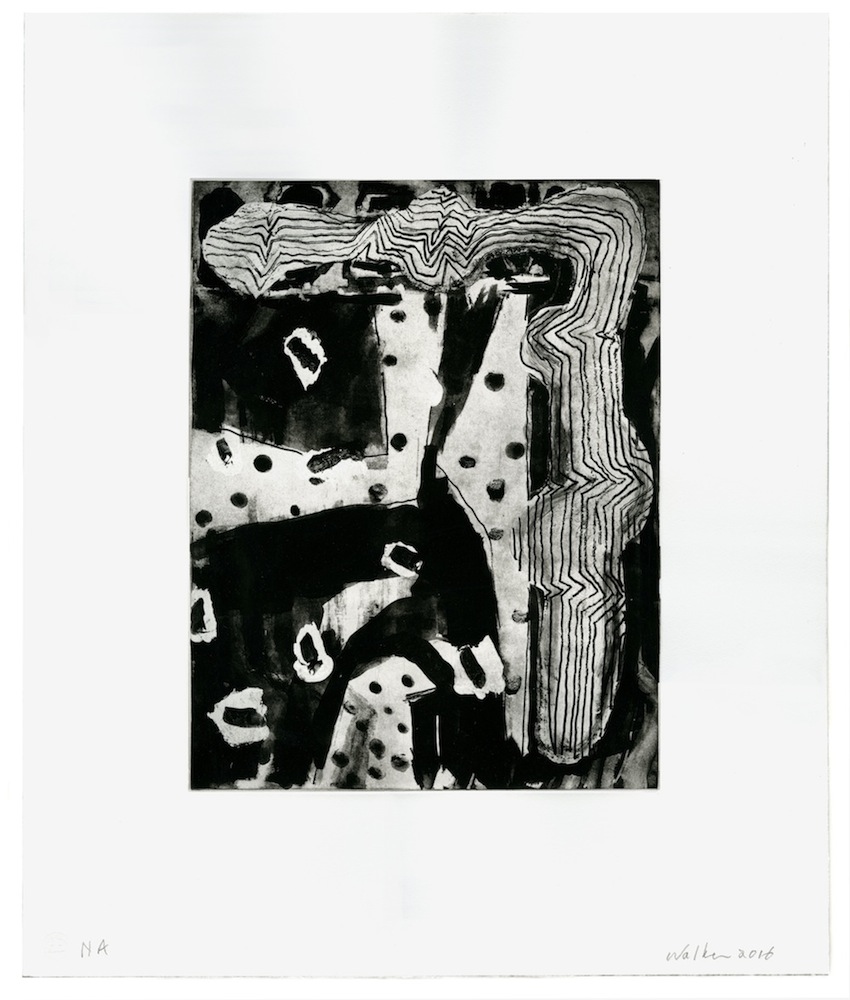

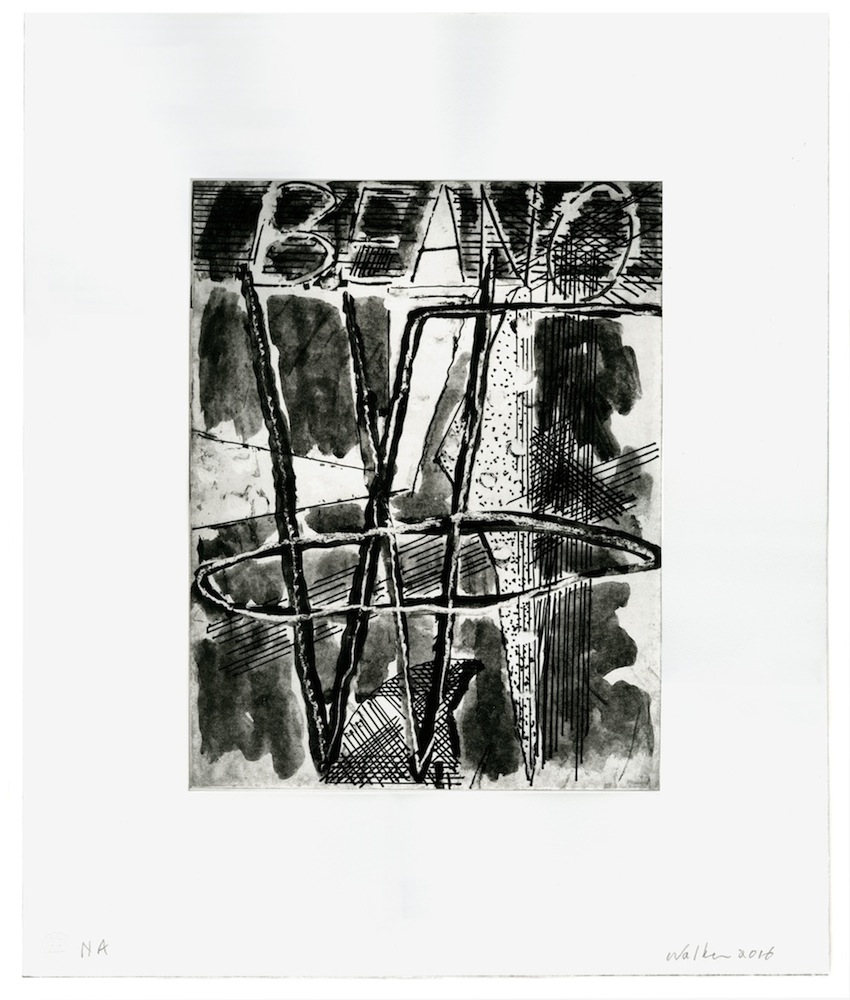

John Walker, Caitlin Lee #5, #7, #8 and #9 (2016). Image at columbia.edu. Image courtesy of the artist.

Walker, whom one critic described as “one of the standout abstract painters of the past 50 years,” is 78 and lives in the northerly state of Maine in the USA. Between 1993 and 2013 he was Professor of Art at Boston University School of Visual Arts and Head of its graduate program in painting and sculpture.

Born in England, his connection with Melbourne dates back to the late 70s and he was Dean of the VCA School of Art between 1982 and 1986.

His legacy lives on, not just in the students and faculty members he influenced but in the studio and gallery complex, Gertrude Contemporary, which he kick-started in 1985 and which is still going strong.

So it seems fitting that I meet up with him in the Norma Redpath studio, in inner-city Carlton, where he’s enjoying a month’s stay as artist-in-residence and showing his wife, artist Kayla Mohammadi, around Melbourne.

Redpath, a sculptor, left her workplace and residence to the University of Melbourne; in September 2017, Gertrude Contemporary and VCA, which now manages it, initiated a joint residency for international artists here.

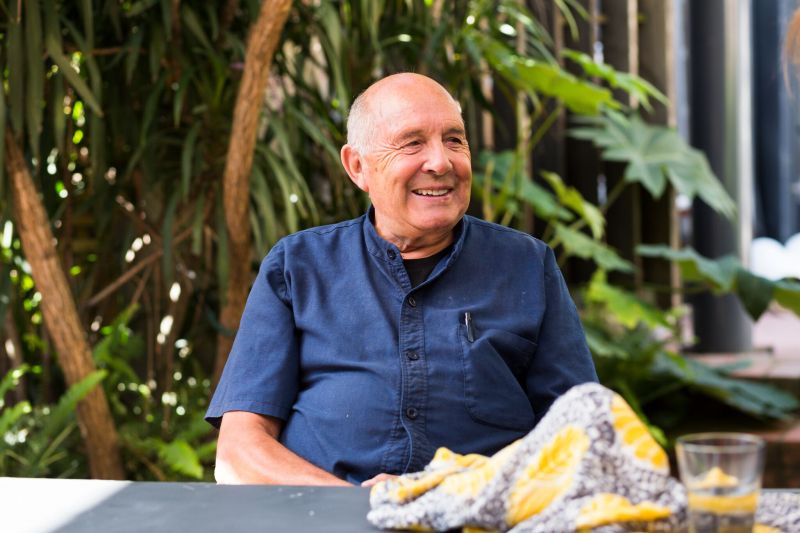

Walker’s sitting in a leafy courtyard at a table dappled with sunlight. Behind him, from the wall outside one of the studios, he’s hung large sheets of paper and, from the look of things, has been busy, with paint and charcoal, on a series of black and white works.

Just as at his American home by the sea in South Bristol, he says he keeps up a daily routine of heading for the studio, reading the papers and then getting down to work.

“If you’re not there it ain’t gonna happen,” he states matter-of-factly, in a voice that still bears strong traces of the English Midlands and the city of Birmingham where he grew up in the 1940s and 50s.

At both the VCA and at Boston he kept a studio in the art school and the door was always open to students. It was part of a larger philosophy of engagement and seemed only fair he says.

“If I could walk into their studios any time of day or night, I thought they should have that privilege with me.”

One of the lessons he hoped they’d learn, he explains, is that an artist paints a lot of dud work and that failure is a vital part of the journey.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

“At the VCA it was important that students should see someone who’s a so-called professional and how they go about making their art and the sheer amount of art they make … there should be the expectation of a lot of failed art which is good for them, because if they try and make a finished work every time they’re going to be a very bad artist.”

There seems to be a general consensus in the art world that Walker is a very good artist.

In 1985 he was a finalist for the Turner Prize; more recently, at the Yale Centre for British Art he was included in its 2010 exhibition “The Independent Eye: Contemporary British Art from the Collection of Samuel and Gabrielle Lurie” in a select group of post-WWII painting luminaries including Patrick Caulfield, Howard Hodgkin, John Hoyland, R. B. Kitaj and Ian Stephenson.

But success came early for Walker and he’d had his first solo show at London’s Hayward Gallery by the time he was 29, in 1968. As he puts it drily, he was “exhibiting with the big boys and girls.”

By the 1980s he was one of Britain’s most successful mid-career artists, with solo shows across Europe and the US including at the Hamburg Kunstverein in 1973 and the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 1974.

Sandwiched between those exhibitions, he’d also represented Britain at the Venice Biennale in 1972.

His painting career wasn’t the primary reason the VCA was keen to recruit Walker however; he’d also taught at some of the top schools in London and New York and been a visiting Professor at Yale University’s new Graduate School of Art and Architecture at New Haven.

It was in 1977 that his association with Australia began, with the Powell Street Gallery. Its dynamic co-director David Rosenthal, who was also a medic, had seen his work in New York and arranged for some to be shown at the South Yarra space.

Walker had also got to know the art historian Patrick McCaughey when they were both Harkness fellows in New York in the early 1970s. McCaughey went on to become the first professor of Fine Arts at Monash University in 1972. They kept in touch and in 1979 McCaughey offered him a Monash residency.

It was there that he had met his future wife, academic and art critic Memory Holloway. An artist’s residency at Prahran College of Advanced Education was arranged for the following year and the scene was set for a more permanent move to Australia. He says he left the UK gladly, although he knew he was waving goodbye to the British art world: “Basically it was the end of my career in England. The English, if you don’t let them love you they don’t like you anymore.”

Walker’s appointment to the post of Dean was a breath of fresh air says VCA’s current Head of Art, Jan Murray. “He was generous and encouraging,” she says, and “had a quiet authority that came from his international achievements…he had nothing to prove. He shifted the culture and once done it couldn’t be reversed.”

Walker says that his aim was to raise the bar higher.

John Walker, Walker Form with Yellow Shield (1986-87). Reproduced courtesy of the artist.

“I taught at Yale and the Royal College and they were like the elite institutions, and I was told that the VCA was an elite institution so I didn’t think there’d be any difference and in many ways there wasn’t, but I did feel that the expectations for students and to a degree the faculty wasn’t as professional as it was, say, at Yale.”

Norbert Loeffler, Lecturer in Critical and Theoretical Studies and one of the VCA’s longest-serving staff members, is less circumspect; he says that by the time Walker came to Melbourne, the city had several art schools and the number of students and professional artists had also grown considerably. The VCA was not doing well, he says, and Walker brought a much-needed dynamism and educational rigour to the college, which at that stage offered scant teaching of theory or history.

“In the late 70s and early 80s [the VCA] had started to drift and there was no compelling energy,” says Loeffler. “He was the ideal person; he came, saw it and said ‘we’re running specific classes, regular tutorials and a proper art theory and history program … we went from one class per week to 11 in one year.”

Walker says that although some faculty members were initially critical of his appointment – “people who didn’t want an Englishman running the school” – his approach combined appointing young teaching staff for energy (many young sessional teachers were brought in including Jan Murray, Howard Arkley, Bill Henson and Phil Hunter) and older ones for wisdom, and the “work hard party hard” approach won opponents over.

“[They] eventually came to the party because they could see the students were having a great time and they were learning so much,” he says.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

He also wanted to break the idea that the best art was being made elsewhere.

“When I started here, people used to look at me incredulously when I said ‘you don’t have to go anywhere’.”

One of Walker’s lasting legacies was setting up Gertrude Contemporary in 1985. Then known as 200 Gertrude Street, the combined studio and gallery complex in Fitzroy was a first for Australia.

The former textiles factory had been offered to the Victorian Council for the Arts (as it was then called) and Walker brokered a deal for a year’s rent with the building’s owner, Philip Cormie, which included one of his paintings and $10,000 of his own money.

Of his beneficence, he says: “If nice things happen to you, you should give back, and people had been terribly generous to me.”

The complex was a response to the isolation experienced by artists post-college, says Walker.

“I was concerned that my graduate students were not being supported once they left school,” he says. The deal, explains Walker, was that it was open to all art school graduates, not just those from VCA; that each artist had to pay for power and that they couldn’t stay for more than two years.

The first director of the exhibition space was Louise Neri, currently a director of the international Gagosian Galleries.

After getting the ball rolling, he then left it for others to run, including his then-wife, Holloway, who was co-chair.

Murray, who had one of the first residencies, said the Gertrude Street complex reflected Walker’s knowledge of similar ventures overseas, including the collective PS 1 in New York.

Its exhibitions soon became a magnet, she says, in an era before the explosion of artist run initiatives in the 1990s.

“He supplied a destination and it was ecumenical. We needed a network and a community and it was pretty amazing in terms of the vision John lent and the generational focus it gave. A lot came out of it.”

Earlier this year, Gertrude Contemporary left its inner-city premises and has relocated to Preston. It maintains its two-year studio residencies and has stuck with 16 of them, as in the original building. Mark Feary, its current director, says it’s still unique in an Australian context.

John Walker at the Norma Redpath Studio. Image by Drew Echberg.

“Having a community of artists forms deep connections between them … it’s always done very well as it fights against hermetic practices,” he says. The new space might lack the grungy charm of the former, he adds “but it’s taken its history with it and for the first time we’ve been able to architecturally develop the spaces.”

Walker is keen on things developing, and against organisations becoming too bureaucratic. He’s glad that Gertrude Contemporary has moved on.

His time in Australia sparked new ideas; the paintings and drawings he did here include his Oceania series and his Prahran Etchings as he soaked up Australian and regional cultural influences. And he’s continued to exhibit here too, with a show at Tim Olsen Gallery, Sydney, in 2012.

He muses on the difference between the art he did as a young man and the art he’s making now. Is he a better painter? I ask.

“Different. One of the things I’d tell my students is ‘you can’t paint an old man’s painting. You can paint a 21-year-old’s painting and I can’t paint a 21-year-old’s painting, only an old man’s one. But a masterpiece is equally available to both of us.’”

And although he cautioned his students that many artists commit themselves to “a very lonely life, mostly in a room on your own” he says that if you dedicate yourself wholeheartedly there’s nothing better.

“Look what it gets you if you really do it; it gives you a wonderful life. I feel blessed.”

By Fiona Gruber