Based in Kyushu, the southern island of Japan, Makoto Kagoshima’s celebrated ceramics are a fusion of design and heartwarming motifs making each object a unique, one-of-a-kind work of art. His hand produced and decorated works are designed with a variety of plants and animals remembered from his childhood. They speak of whimsy and elegance and an almost quixotic sense of a fleeting pleasure somehow caught. Makoto first showed with us at Messums Wiltshire as part of a collaboration with John Julian Ceramics where he was decorating plates for a joint show of their work.

We are delighted to represent Makoto’s work exclusively in Europe and to be hosting his second ever solo show.

Describing the kind of Japanese paper he uses to make his prints, Francesco Poiana says; ‘It is very thin and also very delicate. I like its feeling of lightness and also the rich tradition and history of paper from which it comes, which has had such a big cultural influence in the West; van Gogh did paintings inspired by Japanese patterns as did many other artists.’

‘The Japanese give as much importance to the empty space as to any images in a work of art. It is the opposite of the medieval Western concept of horror vacui where every inch is covered.’

Born in Faedis near Trieste, the son of an architect and winemaker, Francesco Poiana attended the Academy of Fine Arts in Rome and then the celebrated Albicocca fine art printing workshop in Udine before studying for a Masters degree at St Martin’s College of Art in London where he graduated last year.

The paper he uses is made from the mulberry paper trees and has a shadowy, translucence perfectly suited to the ghostly imagery of his works.

‘If you layer one sheet of paper on top of others they can look like a skin, soft and translucent and sensitive,’ he says.

The works in this show feature man at a crossroads as well as boats and other visual metaphors for life’s endings and beginnings. A solitary figure is seen standing in a wood suggesting our isolation from each other yet our deep connection with other elements of the natural world. These are poetry in physical form, fragments from a mind less ordinary.

We are delighted to support an emerging talents programme for the second consecutive year, the criteria for which is one of talent in terms of making and originality in narrative.

Francesco will join us in the gallery for our regular Tuesday Talks on 10th March…buy tickets

Leading ceramics expert Paul Greenhalgh (director of the Sainsbury Center, Norwich) introduces two of the biggest names in Korean ceramics working today for their debut in London, as part of our focus on Ceramic across both London and Wiltshire venues.

Perhaps time is the single most important determinant in how we understand ceramic. It isn’t just that the discipline has a dauntingly deep and pervasive history – we are aware of fired clay objects from as early as 29,000 BCE – but that we have superb examples of them, from then through virtually every age up to the present. The lasting power of fired clay is unique: no other art has a lineage as ubiquitous or intense as this. Inevitably then, it leans on all contemporary artists who seriously engage with it. Contemporary ceramic has to deal with an ever-present memory, one that cannot easily be elided, and this is an inescapable factor in its aesthetic make-up.

Nowhere is this sense of cultural memory more powerful than in Korea, which has been host to a vital ceramic culture for millennia, and at various points in that long history, has been thought to be unrivalled. It took celadon to heights that even the Chinese struggled to match, and for some of us, the painterly porcelain vases of the Middle Chosun Dynasty are among the greatest achievements of world art. We understand as specific Korean contributions various types of relief and incised wares, and the magnificent form known as the moon jar. In one way or another, contemporary Korean practitioners have to deal with this giant, omnipresent heritage.

As with painting and sculpture, it isn’t always a blessing. Grand canons have the power to stultify experimentation, and to intimidate artists into unnecessary respect and imitation. Nevertheless, the greatest art in the modern period – and especially the greatest ceramic – has been that which forms a relationship with the past – absorbing, commenting, challenging, and even denying its implications – in order to make art that moves us on.

Ree Soo Jong (born 1948) has long been recognized as one of Korea’s principal ceramic artists. Interestingly, while his output for several decades has essentially been about the vessel, in the extraordinary context he grew up in, his formation as an artist was quite different. His early reputation was driven far more by a sculptural approach to practice. Through the 1970s and 1980s, he developed a wide repertoire of organic, raw, abstract forms, which occasionally tipped into architectonic structures. He also worked with the human figure. Vitally, he has always been engaged with painting and drawing, running this thread alongside his ceramic activity. He is the painterly draftsman par excellence, and in many respects, drawing underpins everything he does.

He occasionally worked with the vessel through his earlier career, but it was really only from the mid-1990s that he committed to it in an ongoing, obsessive way. Thus, he previously had a career of pushing, testing, experimenting, in which clay was moved through a wide repertoire of idioms, before the determination to focus this exploration on pots.

His work in the current exhibition essentially comprises of a number groups, each of which is an essay on the moon jar. The artist doesn’t say a lot in front of his work, but when I met him I his studio, he tellingly pointed out that traditionally, the rounded form of the moon jar was achieved by throwing two bowls, and then joining them together to create a spherical form. The join would be smoothed out, to hide the process. Soo-Jong frequently exposes the join to make it a core element in the vessel. He then uses his extraordinary technical control to push the form into new terrain. His language of lines, splashes, drips, dints, tucks, dents allows him to transform the moon jar into an emotive arena, a site of unmediated expression.

One of the artist’s great signature pieces is a tall white vessel derived from a moon jar, with a single dramatic gestural black brush mark across its face. It is a spectacular, existential statement about the fusion of past and present, and a quintessentially Asian – Korean – approach to the painted vessel. A sublime level of confidence brings thrown form and painted surface into unison, and painting and pottery become the same thing.

This method and philosophy of the painted vessel was known to European by the later 19th century, but it was most effectively brought to Europe by Bernard Leach and Shoji Hamada, who worked together in Japan. They returned to Britain in 1920, exactly a century ago, and profoundly impacted Western studio ceramic. So the visual language at work in Soo-Jong’s moon jars is now a truly international idiom. But few have ever practiced it like this: he has taken the idiom, and brought it profoundly into the 21st century. His moon jars are among the greatest pots of our times.

Ree Soo-Jong knew Hamada. Much like the Japanese master, there is a profound straight-forwardness in his vision of practice. Art historian Choi Gong-Ho commented that

Ree Soo-Jong does not use exaggerated rhetoric when he talks about his works. This implies that he thinks that true works of art are created when working with clay with your own hands rather than playing with words. He believes a day’s physical labour is far more honest than ten seemingly great concepts. So, he says, working is his life.

He is acutely aware of global developments in artistic practice, and of the ideas that underpin it. But his life is squarely based in making things.

This sense of artisanship, of doing, seems to be part of the Korean attitude to culture. Lee Hun Chung (born 1967), describes his attitude to practice in much the same way as Soo-Jong. He tells us that

“I like people who think with their hands and talk with their hands, people who genuinely think of the works themselves as goals.”

A kind of physical cognition: not a denial of ideas, but rather, an assertion that they cannot exist in isolation from the object. The role of the individual artist is to expose ideas through materials.

A generation younger, Hun Chung’s national reputation is as an artist who has engaged with conceptualist approaches to practice. He often works with large scale installations, that deliberately confound any demarcation between the various disciplines. Art critic Chang Dong Kwang tells us that “Lee is a potter, sculptor, designer, architect, painter, installation artist, poet, and labourer, because he is full of raw human character”. He also refuses to acknowledge any meaningful space between abstract and figurative art. Much of his work is multi-media, with large-scale ceramic sculptural forms at the heart of things. Running through all of this, is a socially-engaged range of imagery. The artist tells us that: “it feels good to live as an artist as a member of society, no more, no less”. His work resonates with what he finds around him, and is driven by an ongoing commentary on life. While there is subversive wit at work, the overwhelming feel of the whole is invariably of a joie de vivre, a gladness to be around, and alive.

As part of this creative vortex of activity, the artist still engages with the vessel, and ceramic as a material of architectonic and design potential. Over the last period of years the artist has developed an extraordinary range of furniture, effectively by expanding the role of the thrown vessel. His chairs, stools, tables and daybeds are created from modeled and thrown ceramic. Large vessels become stools, or the support for a day-bed. He uses the related technology of cast and polished concrete to create the flat planes to make the furniture work. More classically, large planters fill interior space, and function as major features in interior space. This work is the core of the current exhibition. And interestingly, he is still engaged in production pottery, running BADA, a company that produces a range of wares for a wide audience.

The Korean ceramic scene is one of the brightest and most complex in the global arena, and it remains at the heart of the national culture. The country boasts impressive ceramic theme parks, and it isn’t by chance that the world’s most important regular international gathering of ceramic art is the Gyeonggi International Biennial, near Seoul. When we peruse the work of these two extraordinary masters, brought to England in quantity for the first time, by the Messums Gallery, we realize why.

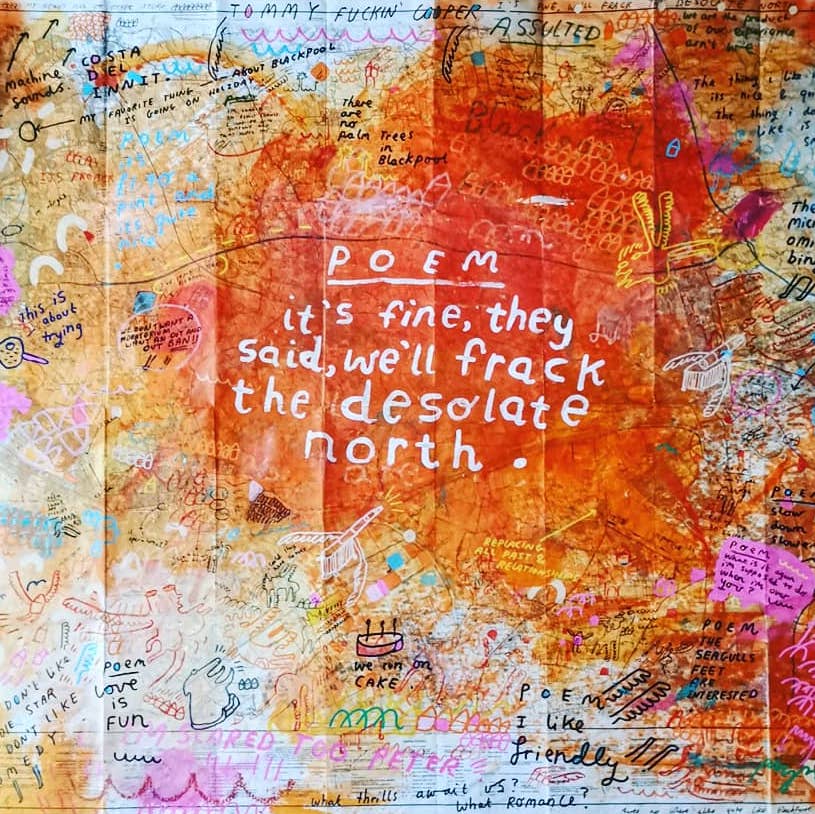

Gommie’s pictures are a testament to one of the most extraordinary years in British history. We have had the vote and these are the first responses from an artist at the coalface of an area that was once a Labour heartland.

Gommie started to make these pictures during one of the lowest ebbs of his life a couple of years ago when, with no permanent address, no studio and only a tent to sleep in, he felt compelled to start walking.

Hitching a lift from a friend to Dover he set off for the north of England but as he walked he started jotting down notes about his encounters with the people he met and noted their comments on the Ordnance Survey maps he was using to navigate his way. At the same time he kept up an upbeat dialogue on Instagram, but, warming to his venture he still had no money so he applied to the Arts Council for funding to continue it. They turned him down so instead he turned to his Instagram followers which were rapidly growing in number who supported him through crowd funding. Last October he won the Saatchi Art Prize for best newcomer and his work is now with Soho House Collection but this is his first project with Messums London.

Gommie’s works are testaments to the joys and tribulations of the people of all walks of life that he has met – their insights, wisdom and often, suffering which they have shared with him and which he has turned into iconic pictures of colour and life.

His work is not easy to categorise; it combines text-based art, land art, performance all of which can be enjoyed at Messums London at 6pm on February 8 when Gommie will hold a performance and share experiences from his findings.

An exhibition of pictures by one of the most distinguished observers of the British landscape, Norman Ackroyd, will be on show at Messums in London throughout January. Twenty-two aquatints and etchings of the Yorkshire countryside – from the snowy plains of the dales to the shadowy presence of Whitby Abbey – will reveal the majesty not only of the landscape of the North but of Ackroyd’s technical skill.

After leaving the family home in Hunslet, Leeds, to take up a place at the Royal College of Art in 1961, Ackroyd has built a reputation as one of Britain’s most highly regarded printmakers.

He made his first etching at Leeds College of Art 60 years ago before winning a place at the Royal College of Art in London where there were 15 other students from Yorkshire, including David Hockney.

“We brought our Yorkshire accents and our work ethic with us’ he said.

Although Ackroyd now lives and works in London he visits Yorkshire often, working in plein air, outside in all weathers, making a watercolour in situ before creating an etching and ensuing prints in his London studio.

This exhibition features a views of Harewood House, Thirsk Hall, Thimbleby, the valley of Wharfedale, the plains of North Riding and Bempton Cliffs – all depicted with Ackroyd’s characteristic muted, monochrome tones that allow the viewer to feel the energy and essence of both familiar and faraway landscapes without the distraction of colours.

He attributes his love of the region’s rural landscape to his brother, who was 12 years older than him and a keen fisherman.

They used to catch the 4am milk train from Leeds up to Settle and while his brother cast his line onto the River Ribble, Ackroyd opened his sketchbook.

Features of the landscape are picked out with an exacting focus yet fluency, born of years of making drawings in all matter of materials, distilled into the aquatints for which he has become so celebrated.

Now a Royal Academician, works by Ackroyd are in a number of major public collections including the Tate Gallery and the Museum of Modern Art, New York. During a recent BBC documentary he was described by the writer Robert Macfarlane as creating ‘astonishing’ works. ‘They take me to those places,’ he said.

As one of the leading contemporary figurative artists working today Antony Williams is dealing uniquely with matters of reflection and thoughtfulness in a context embedded in tradition and provenance. This series of beautifully conceived works perfectly examples Williams’s recent development towards, not only the human psyche, but how this relates to the natural landscape.

Williams’ pallet, typical of the hue of tempera, is subdued yet made luminous and incandescent through his use of minute brush strokes, a semi-pointillist technique, that dance together on the canvas creating an unparalleled depth of colour. Author and curator, David Boyd Haycock describes Williams’ style regarding ‘Umbrian Swimming Pool’ as ‘like a collision between David Hockney and the early Italian Renaissance master, Piero della Francesca.’ From Hockney comes the quality of colour and curious sense of unease and from Piero della Francesca comes the precision and hue of egg tempera along with the ‘very real aura of a hot Italian landscape.’

In the late 1980s through to the early mid 90s Antony was working like David Bomberg and Frank Auerbach, making large gestural views of London in thick charcoal and oil paint. Something of those powerful gestures still lingers in his work, though now each is writ incredibly small in an infinity of tiny strokes. It is this same process of almost endless mark making that lends the instantly eye-catching power to his portraits. We seem to see the actual flesh beneath the skin, and the veins within the flesh, and even the water in a sitter’s rheumy eyes. And here again we encounter the collision of old with new, as Lucian Freud seems to meet the early Flemish portraiture of Jan van Eyck–both painters that Williams greatly admires.

Daniel Agdag, an artist and filmmaker from Melbourne, creates models that come to life through the medium of stop motion animation. As static objects, however, these pieces invite close personal inspection and maintain suggestions of whimsy and narrative. Agdag’s pieces make no attempt to conceal the mechanisms and materials of his process. For Agdag, cardboard is a tool with endless potential. These pieces are part architectural model, part movie set, part artifact hinting at excavated civilizations in the miniature, or museum relics of undiscovered worlds. On Wednesday 3rd July there will be a talk and tour examining Agdag’s imaginative creations allowing you into the universe of the miniature.

Agdag’s practice sits at the nexus of sculpture and motionography. He creates highly detailed sculptural pieces that have been described as architectural in form, whimsical and antiquated in nature and inconceivably intricate. Daniel predominately works in cardboard. Drawn to its utilitarian origins and monochromatic presentation, he creates a paradox of fragility and strength with structures that resemble architectural forms and machines.

Tuesday Riddell’s work takes us down to the forest floor and a glorious insight into the world that captures her imagination, that ethereal nocturne when all cycles of life and death carry on with rarely a watchful eye. However it is also her unique craftsmanship in the ancient art of japanning that catches the eye. Tuesday’s first show was in our Emerging Talents exhibition last November and then at the London Art fair this spring. It is with great pleasure that we welcome Tuesday to Cork street for her debut show with Messums London.

Riddell’s work doesn’t tow the line between the decorative and fine arts, it dances back and forth over it. Her pieces play with these two often opposing worlds – the narrative driven and fantastical world of fine art and the world of applied arts through use of traditional methods and ornamental surfaces. Riddell’s work is rooted in the hours of dusk and nightfall. Worlds of detailed miniature, these scenes are evocative of dreams that do not shy from themes of decay and mortality. Through processes of japanning and chinoiserie these creations are grounded in dramatic tones of black and gold. The ornate surface of the works, together with the depth of narrative, are traversed together in a rare marriage of the imagined world and the decorated surface.

Tuesday Riddell graduated with a BA (Hons) in Fine Art Painting from City & Guilds of London Art School. She has concluded her Painter-Stainers Decorative Surface Fellowship at City & Guilds – the only Fellowship in the UK that provides specialist training in the craft of decorative surface techniques to ensure that endangered skills are kept alive and vibrant in contemporary practice, focusing on historic techniques such as gilding, japanning, chinoiserie and marbling.

Danish artist Malene Hartmann Rasmussen works with figurative narrative sculpture and installation, creating work from individual hand-modelled ceramics and found objects. She is part of a vanguard of artists who choose not to define themselves by discipline or craft but instead blur the boundaries between Applied Art, Design and Fine Art, with exceptional hand-craftsmanship at its core.

This exhibition is a chance to preview a new body of work that will be the highlight of Beyond the Vessel at the Koç Foundation’s gallery, Meşher, Istanbul taking place during the Biennale in September 2019 and curatorial director Catherine Milner will introduce the exhibition and the accompanying catalogue for the launch on Tuesday 16 July.

Reflecting her Danish ancestry and the tales of northern European folklore Hartmann Rasmussen’s work is a metaphor for the relationships of her past – both with her family and the adolescence she left behind. The brightness, playfulness and immediate visual appeal belies a darker narrative where reality and daydreams are merged.The installation deals with ideas of worship, animism, ritual and the supernatural as well as ghosts. The title of the installation is Fantasma – the Spanish word for ghosts – and the works reflect the time honoured use by human beings of figurative sculpture as talismanic objects to help deal with feelings such as fear, misery, anger, lunacy and grief.

Hartmann Rasmussen cites her greatest influence as her childhood – one that involved an alcoholic father and a mother who suffered from bipolar disorder and was regularly hospitalised. “It is not specific tales from Scandinavia but more the different sides of human nature and the creatures that represent these that interest me”, she says. “In some of the stories I have read and I remember from my childhood you have to be on good terms with the trolls and other creatures then they will help you in times of trouble. Often when people help the trolls with something, the trolls then pay for the service with gold. If you don’t keep your promise the gold turns to rocks… I find the magical aspect of that kind of narrative, fascinating.”

Much of her inspiration comes from the books she read as a child too. “When researching my recent installation Troldeskoven (In the Troll Wood) I got hold of some old books from an antiquarian bookseller with stories and sayings told for generations from mother to child in rural Denmark. The stories revolve around trolls and subterranean people on the island of Bornholm – the island I lived on for three years while studying ceramics – and some locals still believe in them. In the daytime the trolls live inside rocks or inside tumuli; the grassy mounds of earth raised over Viking graves that are dotted all over the landscape. At night the grass and soil rise up on glowing poles forming a roof. Inside you see the trolls dance and drink, and if they invite you in to drink with them, all the soil and grass will fall down and bury you inside forever. The Danish word ‘bjergtage’ meaning ‘being taken by the mountain’, originates from these stories. ‘Bjergtage’ is the Danish word for bedazzle. The strong bond between the myth and language is something I find fascinating.”

This new body of work – her first to be on public exhibition since she was Ceramics Resident Artist at the V&A in 2018 – is inspired by Danish frescos called kalkmalerier, that depict demons and fabeldyr or fantastical creatures found in Danish churches dating from the high and late middle ages.

‘I love the naivety of them’ says Hartmann Rasmussen, ‘there is no perspective and the dimensions are all wrong, but they can be very elaborate and detailed’. Some figures such as Violet Sleep reflect the Danish idea of ‘Hellmouth’ the entrance to hell, which appears in churches in the shape of a monster with an enormous mouth and teeth.

There are also fantastical creatures such as Sciapod; a strange being that feeds on people’s heads that has one large foot that it uses for shade as it lives in the desert. A key sculpture in the show is the biggest that Hartmann Rasmussen has ever made; a tall, totem-like sculpture of stacked beasts.

‘I am fascinated by the use of magic in the form of transformation, spells, offerings and sacred ritual objects and take in some of those ideas in my work in general.’

Photography credit: Sylvain Deleu