Biography | Studio | Archive | Creative Legacy

A collection of items, research and objet trouvé

When Elisabeth Frink is mentioned, most will refer to her huge bronzes like Walking Madonna in Salisbury or Paternoster in Paternoster Square near St Paul’s Cathedral in London. Less frequently, do we think about the beginning of her creative process, her drawings, some of which were never made into sculpture.

In November 2020, we were introduced to two marvellous examples of her drawings and also to a personal story which brought us closer to Frink. As mentioned in Sculpting the Sculptor, the owner’s parents had been friends with Elisabeth Frink and her 2nd husband Ted Pool. The piece on paper is part of a group of drawings of animals which were never made into sculptures, the language of mark-making in two dimensions perhaps suiting the subject matter better.

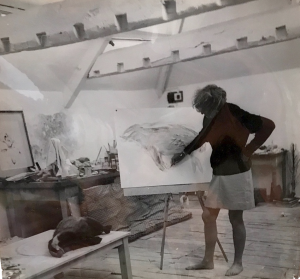

This remarkable photograph provides the clue into the story that accompanied the works of the Hare and the Boar. Here is a setting that is likely to be the studio of the owner’s father featured in Sculpting a Sculptor. Frink is portrayed in the process of a rather lurid and probably challenging drawing. Frink is drawing a dead badger, found while the Owner’s sister was out riding. This may be the same drawing as sold at Christies in the 2014 Modern British and Irish Art sale. Edward Lucie-Smith’s book Elisabeth Frink: Sculpture since 1984 & drawings, features not only a page showing other dead animals but drawings of a badger and a version of the hare. At the back of the book in the catalogue raisonné of drawings, many dead animals feature on the list in the mid-1960s.

The photograph supports the anecdote that came with the photograph, chiefly that the owner’s sister mentioned having seen the badger and his father went out to collect it after having presumably been struck by a car. The poor animal was then put into the freezer along with a hare (its origin not relayed) both of which reappear in a series of drawings (of which there are three in total we think of the hare).

It is very interesting to note Frink’s apparent ease at making art away from her own studio. Her shoes are off as she stands in front of an easel, with the badger on the table. There is an unusual informality of an artist at work not in a studio of their own which sparks many questions as to what the purpose of drawing is. Perhaps it’s to develop their skill at animal anatomy or perhaps it is for pleasure. As mentioned there are a few versions of this hare drawing, it shows the time Frink put into her drawings, using each version to capture a different side and aspect of the animal. As these drawings never became sculpture, we could consider this as evidence of Frink drawing for pleasure and study rather than for a larger sculptural project, ensuring her continual development as an artist.

.

.

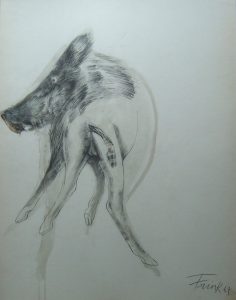

Along with the drawing of the hare came also came a drawing of a boar which was completed in 1967 but when it ended up in the owner’s parent’s collection is unrecorded. While the Owner’s boar drawing was not created for her 1957 Harlow sculpture Boar, it does highlight the progression and stylistic changes from Frink’s drawings to her sculptures. Boars reoccurred regularly in both Frink’s sculpture, drawings and lithographs from 1957 until the mid-1970s. Annette Ratuszniak commented ‘In 1955 Frink married the architect Michel Jammet, from a French family that lived in Dublin. When travelling around Ireland, Frink saw a lot of Celtic sculpture. Although not drawing directly upon Celtic imagery or myths, she was interested in the psychological relationships between humans and animals.’[1] The boar symbolises warfare and aggression in Irish mythology, two traits which it could be argued Frink deemed shared by humans. This particular drawing was made in 1967, which was the year she moved to France. In the Camargue Frink would have regularly seen them moving around. The Owner’s family remained friends with Frink for the rest of Frink’s life and his sister and mother went to visit Frink at Le Village. This house and studio was located near Uzès and Frink lived there between 1967 and 1973 before moving back and buying Woolland and building the Blue Studio.

.

.

___________________________________________________________

[1] Annette Ratuszniak (ed), Elisabeth Frink, Catalogue Raisonné of Sculpture 1947-93, Lund Humphries, Farnham, 2013, p.56